The Importance of Price Signals

Originally published: December 2021

When price inflation occurs, it can be a very challenging time for everyone.

In that type of environment, prices of goods and services often go up faster than wages, and the public and policymakers wish to constrain them. Historically, when price inflation becomes rampant, policymakers tend to put in place price and wage controls to try to tame inflation, but those don’t have a good track record of working out well.

As an analogy, in nature pain is important, even though pain is undesirable. Pain is a useful signal to avoid certain threats or certain behaviors. If we are injured, pain is a nuisance, but it’s a valuable nuisance that trains us to rest our injured area so that it can heal properly.

Similarly, price changes are often undesirable, but they are useful in the sense that they provide us with information that allows us to respond and fix the problem in the long run. This article explores that concept.

Inflation: Mysterious or No?

I see financial media often say things like “the causes of inflation are still a mystery” and that “nobody really knows what causes inflation”.

I disagree with that. There are tons of things I don’t know, and perhaps many things that are inherently unknowable, but price inflation is not exactly the most mysterious thing out there.

We know a few basic things that we can put together:

1) Broad money supply and price inflation are rather correlated.

The most precise way to phrase it is that rapid money supply growth is necessary but not sufficient to cause widespread price inflation.

In other words, price inflation always tends to happen when money supply grows very quickly, but a rapid growth in money supply does not always lead to substantial price inflation.

In the United States, for example, we can look at the 5-year rolling growth rate of M2 and CPI over the past 150 years:

Data Source: MacroHistory.net

Every time there was a broad and persistent rise in price inflation (orange line), there was also a substantial growth in broad money (blue line). However, there were periods where broad money went up a lot, and price inflation didn’t necessarily follow.

The first disconnect between the two was in the late 1800s and early 1990s. Land was cheap and almost unlimited for settlers (as natives were displaced through conflict and disease), and the industrial revolution provided all sorts of modern technology including the proliferation of railroads and electricity that provided a powerful form of technology-driven price deflation. So, despite substantial bank lending and financialization, it was mostly productive and thus did not result in too much money chasing too few goods.

The second disconnect was in the 1990s through the 2010s, where the US experienced a large gap between labor productivity and wages as a result of offshoring and automation. Corporations performed geographic arbitrage by firing domestic workers and hiring much cheaper foreign workers in sweatshops due to better communication technologies, infrastructure, and foreign development that made that possible. In addition, the definition of CPI was changed substantially as well to include a different basket of goods, and there was a rapid rise in cheap processed foods that could more easily be mass-produced, at the cost of being less healthy. Money supply could go up a lot without necessarily causing broad price inflation as measured by CPI.

We see examples of this internationally as well. Here is Australia:

Data Source: MacroHistory.net

Again we see a very tight correlation between broad money and price inflation over most of that period, although we do see a disconnect over the past thirty years. Australia grew its money supply quite rapidly without experiencing much inflation during that specific era.

This was, once again, due to a period of abundance. Australia was positioned very well next to southeast Asia, as China and other countries rapidly developed and consumed commodities, which Australia was happy to provide. A lot of foreign money flowed into the Australian real estate market in return. Basically, this was another look at the deflationary impact from globalization.

In summary for this point, we can say that broad money supply and price inflation are quite correlated when there is a period of constrained resources, and can become decoupled when resources are unusually abundant for unique circumstances involving some sort of new area of resources or labor rapidly opening up.

The broad money supply in the United States grew by 40% for the two years 2020 and 2021, due to large fiscal stimulus to offset pandemic lockdowns and such. Some degree of price inflation from this was almost inevitable. The questions are how much price inflation and for how long.

2) Commodity cycles and price inflation are tightly correlated.

Next we can follow that logic to look at commodities. This chart shows the 5-year rolling change in CPI vs oil prices:

Data Source: MacroHistory.net

We would see a similar result if I put copper in place of oil there, or a broad commodity index. There were no instances of the prices of everything else going up substantially and persistently while oil and other commodities remained cheap. However, it technically is possible to have high commodity prices without it necessarily causing broad price inflation, if you have major deflationary forces elsewhere (such as the 2003-2008 period of high oil prices offset by deflationary forces of globalization, along with new ways to calculate CPI).

Humanity has access to a fixed amount of commodity and infrastructure resources at any given time, and replacements take money and time to develop if not well-planned for in advance. When commodities are cheap, there is little incentive to invest in bringing new resources to production. When commodities are expensive, there is tons of incentive to do so. So commodity shortages work themselves out over time, but typically with a big lag.

As these two points combined show, in order to see broad and persistent price inflation in an economy, we generally need two things. The first is a persistent rise in broad money supply and the second is a physical constraint on our ability to produce more commodities, goods, or services cheaply.

Inflation is not a huge mystery if you track both the money supply and the natural resource capex cycle. That doesn’t mean you can precisely say which specific month inflation will appear in, or exactly what magnitude it will reach in a narrow timeframe, but it means you can analyze if an environment is ripe for high inflation or not.

3) There are two main ways to create broad money.

Current fiat-only currency systems, as well as prior gold-backed paper currency systems, expand their money supply in one of two ways.

The first way is through bank lending. When banks create loans, they spend new money into existence, with the caveat being that the new assets they created are subject to credit risk so they should create this new money prudently.

The second way is through large fiscal deficits that are monetized by the central bank and the commercial banking system. In other words, the government can directly spend a ton of money into existence. When done through the fiscal channel, this money doesn’t just get into bank reserves; it gets out into the broad public savings and checking accounts and into circulation.

I went into detail on these mechanisms in my article on money creation from 2020.

This chart shows the year-over-year change in the broad money supply as a percentage of GDP (gray line), compared to the year-over-year change in bank loans as a percentage of GDP (blue line) and fiscal deficits as a percentage of GDP (orange line):

The growth in money supply during the late 1880s and early 1990s was entirely driven by bank lending. In contrast, the 1910s growth in money supply was mostly from fiscal spending on World War I.

The 1920s money supply growth was once again from bank lending, which collapsed via defaults in the 1930s. The 1930s saw a sluggish money supply because fiscal deficits and loan losses basically cancelled each other out. The massive 1940s growth in the money supply was from fiscal deficits.

In the 1950s and 1960s it was bank lending again. By the 1970s, it was a combination of bank lending and fiscal deficits.

And then money supply growth slowed down a bit in the 1980s and 1990s, and was driven by a bit of both bank lending and deficits. By the 2000s global financial crisis and into the 2010s and 2020s, it was fiscal deficits that continued growing the money supply, which accelerated in the early 2020s.

Demographics play a big role in bank lending. When a large generation such as Baby Boomers enter their house-formation years, that tends to drive a lot of money creation via bank lending. In addition, when a developing country starts from being under-banked and increasingly starts getting banked over time (like the United States in the late 1800s, or India over the past decade), that tends to result in a lot of money supply growth and real GDP growth.

Three Points Summarized

To sum this section together, we get price inflation when either banks lend a lot of money into existence at once (typically a result of a demographics boom or country going from being under-banked to fully-banked), or governments spend a lot of money into existence at once (typically the result of a war, emergency stimulus, or purposeful/mismanaged currency debasement), and when this money-driven demand for goods and services runs into physical constraints such as not enough commodity production or not enough supply chain flexibility. Commodity resources, manufacturing capability, and logistics infrastructure are all very expensive things that can’t adjust rapidly to changes in demand.

Around the margins, there are all sorts of complicated details including human psychology. The “animal spirits” of a society can dictate inflation to some degree based on their behavior. However, we can see the makings of major inflations generally build up in advance for various fundamental reasons, and then how they are handled can determine how high that inflation goes and how long it persists.

Price inflation is complex with several moving parts, but it’s by no means some esoteric mystery. Over the long arc of time technological improvements are deflationary, especially during this multi-century period of energy growth, but rapid expansions of the money supply, resource constraints, demographic bulges, and other factors can cause substantial inflationary periods.

Price: An Instant Signal

Price tells us a tremendous amount about what’s happening and how to reduce the severity of it, even if we don’t know the details.

High prices can be painful but that pain is important to have so that we can respond to it properly as individuals, corporations, and governments.

Let’s consider three examples.

Broken Pipeline

Suppose that 300 miles away, a pipeline breaks, and gasoline stops being supplied to large portions of a US state.

Gasoline at stations quickly run out. A few stations have some fuel left but they double the price and are running out too. Some people who had gasoline stored up start price gouging, saying you can buy their gasoline from them for 3x what it normally costs.

Suddenly, millions of people have a signal about gasoline, whether they have any idea of what happened to the pipeline. Those who don’t need to drive, won’t. Uber prices will spike. Some people have a stronger reason to drive, and are willing to pay 2x, 3x, 4x or more of the normal price to get gasoline.

As a couple days go by, some enterprising individuals or companies from other states will start buying gasoline and driving to this state to sell that gasoline at a big markup. If you are a resident of the gasoline-starved state and can pay 2x, 3x, or 4x for the price, you can get it.

On its surface, this looks really bad. Obviously we have to get that pipeline fixed as fast as possible, but other than that, what can we do to make consumers happier in the meantime?

One option is to blame the price gougers and try to stop price increases. We can pass a law and say, “nobody can sell gasoline for higher than the day it was before the pipeline broke!”

However, that’s a pretty bad option, because that just suppresses the price signal. Millions of people who don’t know each other are currently trying to fix the problem in various ways that complement each other, thanks to that high price level. The pipeline company is trying to fix the broken pipeline so they can start making money again. People who don’t need much gasoline are using less. People who do need gasoline are paying 2x, 3x, or 4x much in order to get it. People who have gasoline stored up from elsewhere are bringing their gasoline to market in that state to meet the needs of those who need it and are willing to pay those elevated rates, and the higher prices go, the more incentive there is for people from a broader area to bring their supplies.

It’s like a big ant colony working together through very rudimentary signals. Or like white blood cells attacking an intruder based on ancient response mechanisms. Price is the single most important signal in markets, and allows for an unexpectedly large amount of coordination, even without direct communication between those who are unknowingly coordinating with each other.

Who would pay 2x, 3x, or 4x as much money for the gasoline? It could be some wealthy people, or some essential businesses who need gasoline to operate and are still profitable at these levels. Maybe you or your wife are pregnant, due to deliver within a week or two, and you want some gasoline in your car in advance regardless of price so that you can get to the hospital when you need to. There are all sorts of reasons why some people might need it more than others and have the means to get it.

In that scenario, the gouging and the spiked prices are not bugs of the system; they are features. They just happen to be unpleasant features, like how pain is an unpleasant feature of the body. The high prices are signaling mechanisms to the entire surrounding area of states saying, “bring us your gasoline!” Prices allow individuals to coordinate in surprisingly complex ways without having to understand anything beyond their own needs and interactions.

After I wrote that section, Europe provided a similar real-world example. Due to a combination of problems, Europe is in the midst of a massive natural gas shortage and extreme price spike. It’s a much bigger problem than a single pipeline for a single US state or few states. Many European manufacturers have had to shut down operations because power prices are so high. If the situation gets bad enough, areas of Europe could literally run out of natural gas in the winter, causing severe power outages and deaths from lack of heating during cold nights.

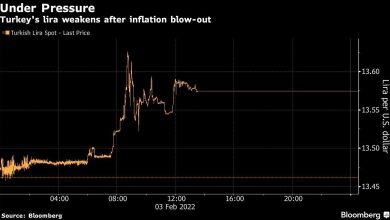

Well, price signals are helping to soften the blow. Europe’s natural gas prices as as of a few days ago were 14x higher than US natural gas prices, and 70% higher than Asian natural gas prices. Asia is having a shortage and price spike too but it’s not as severe as Europe’s at the moment.

So, as Bloomberg reports, US liquified natural export terminals are operating at maximum capacity and are shifting a larger-than-normal percentage of their shipments to Europe instead of Asia:

U.S. LNG export terminals are operating at or above capacity after reaching record flows on Sunday. Asia is typically the top destination for U.S. LNG cargoes, but that has changed this winter with the significant premium for gas in Europe.

That won’t be enough to fix the problem, but it does help by getting more gas to the continent.

Underpaid Truckers

Suppose that trucking is an under-filled job. It’s not particularly desirable, doesn’t pay enough, and people keep talking about how it’s going to be automated away in ten years anyway. However, the shortage is not an emergency yet. It’s just a tight market. People join as truckers but the retention rate is low because the wages just aren’t good enough for the difficult lifestyle.

And then something happens. There is a change in consumer behavior such that they want more goods and fewer services, perhaps because they are stuck at home in a pandemic and have stimulus checks. Suddenly the demand for truckers goes up! But wages don’t rise fast enough.

The shortage gets more and more severe. Shelves go empty. The mismatch gets wider.

People will start paying more for goods, especially parts of the population who can. Those who can’t, get understandably frustrated. There’s plenty of blame to go around. Depending on how they see it, some will blame a supposedly incompetent government, and some will blame the supposedly greedy corporations. And as usual there are probably elements of truth in all of that.

But those price increases are important, because they keep going up, and they keep telling the producers, “pay way more for your truckers if needed, now!”

It’s like that old saying, “the beatings will continue until morale improves”. The supply chain constraints will continue until there are enough truckers. There will be enough truckers when they get compensated well enough relative to the challenges of the job to attract and retain enough of them.

And that applies to all sorts of aspects of the supply chain. Not enough ships? The price is saying to make ships! Are there not enough ports? The price is saying to start making or expanding ports! Not enough retail workers or other supply chain workers? Pay them more to get them incentivized enough to do it compared to other industries!

Negative Oil

Prices going sharply down can send signals too.

During spring 2020, the price of WTI crude oil briefly went to negative $37 USD. Sellers had to pay money to get rid of it, and buyers got paid to take it. It was totally backwards.

Chart Source: St. Louis Fed

Why? Because a sudden massive demand shock occurred, as people locked down and sharply reduced their oil demand in various ways. Flights reduced, driving reduced, manufacturing and construction briefly paused in some areas, etc.

And yet, oil wells are hard and costly to cap. You don’t just snap your fingers and they close or open right away. You can have a situation where there is literally more supply than available storage, and you literally risk having to pour the excess oil onto the ground and get fined for environmental damage. Nobody wants that, for multiple obvious reasons.

That negative price was sending out multiple signals simultaneously. It was telling producers not to drill new wells for the moment, and even to cap some wells where possible. It was telling anyone with an empty tanker, such as a truck or a ship or a train or whatever, to come get oil because we’ll literally pay you to take it so we don’t have to dump it on the ground.

Again, it was an organizing force to fix the problem on multiple sides.

Exceptions to the Rule

These types of situations would be different if there were some patent or other monopoly-like limitation that allowed an entity to gouge prices for an essential good or service, with no ability for the market to respond. The price gouging ends up being purely extractive in that case, rather than useful for societal coordination and resource optimization.

For example, there have been cases where someone buys a patent for a drug that people rely on to live, and then that new patent holder increases the price of the drug by 10x. There would be no price signal in that case; just a high price that some entity is able to persistently extract from everyone else through legal or financial engineering that goes above and beyond the normal incentive for drug development. That’s why some people make a case for patent laws needing some reforms.

Monitoring the Signals

We can think of price as the solution to a bandwidth problem.

There are various political models that work, ranging from Norway to the United States to Singapore to Japan, but one thing they have in common is that they have price signals. One of the key reasons why a truly-centrally planned economy has never really worked on a large scale, is that a room full of guys dictating prices just can’t keep up with the bandwidth. In an economy with a hundred million people making daily decisions, there are hundreds of millions of transactions per day, and billions of transactions per month.

Each one of these transactions is a price signal and an organizing force that gets people who don’t know each other to work together. They’re saying “we need more oil because we are undersupplied”, or “bring carpenters and electricians to Florida to fix the hurricane damage”, or “pay truckers more if you don’t want your shelves to be empty” or “that’s way too much natural gas, stop sending capital to natural gas producers.” or “send all spare LNG you have to Europe, it’s an emergency and we’ll pay a 14x markup!”

As investors, we can monitor the price signals to see what they are telling us.

For the prior example of European natural gas, which keeps them warm in the winter and powers a significant chunk of their electricity, it is telling the continent that they need to rethink some aspects of their energy policy over the long run. It’s also telling anyone with flexible LNG export capacity to send it over to Europe in the shorter term.

For the past several decades, we have been in a general trend of globalization and commodity supply growth. Outsourcing labor for certain types of manufacturing and even some services from the developed world to the developing world pushed down developed world wages and kept a lid on price inflation. We tapped into a huge pool of untapped labor. By doing so, we sacrificed some societal resiliency to maximize efficiency, which minimized prices. Hundreds of millions of people in developing countries were pulled out of extreme poverty.

And yet, populism is rising over the prior decade, particularly in countries that have persistent trade deficits, including in the US which is the big engine of this globalization. Meanwhile, a large portion of the global supply chain apparatus is based on the premise of perpetual world peace; that US and China won’t enter into a cold war type of scenario with some degree of economic decoupling.

For the past few years, and then fueled by the pandemic and policy responses to it, there have been growing signs that globalization may be topping out for a while, which if true, would be rather inflationary all else being equal. That doesn’t mean globalization goes away, but it means that especially the past 25 years of rapid globalization may be peaking out, which removes a powerful deflationary force from the macro environment.

Price signals tell us which things we need to build more of and which things we need to build less of. They tell us where to send capital, what we can freely buy more of, what we should be more cautious using up, and so forth.

Natural gas price spikes in Europe, coal price spikes in China, supply chain problems in the US and globally, semiconductor shortages, truck driver shortages- all of these tell us what to do. And if we get the message wrong at first, price signals get stronger until we figure it out, like a homing beacon continually pointing us to the right answer. The price signals are imperfect and messy, but useful.

While I would fade parabolas such as what is happening in Europe with energy prices, I am structurally bullish on oil and gas producers and transporters over the 2020s decade because there is lack of major investment in new supply, but still persistent demand (especially out of the emerging world, which consumes far less per capita). I’m also bullish on electrification metals such as copper and nickel over the long run, and generally see an environment that continues to be somewhat ripe for inflationary pressures.

Source link