There’s a heard of elephants in the room

Among the many problems currencies and markets face, there is one which is undocumented: the eurodollar market, which is yet another very large elephant in the room. This article quantifies eurodollars and eurodollar bonds, which are additional to US money supply and credit.

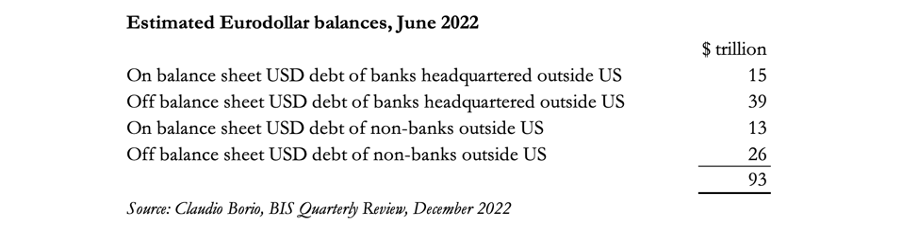

Research by the Bank of International Settlements puts this market at $93 trillion, of which on-balance sheet debt (i.e., customer deposits) of non-US banks is $15 trillion, a sum which should be added to US M2 money supply of $21 trillion for a truer picture of total dollar bank credit. Only a small of this debt is in other currencies.

In this article, I describe the origin of eurodollars and why they have grown to such an enormous quantity. They introduce unrecognised risks to capital markets, and particularly the dollar at a time of growing financial instability. While the factors leading to a Triffin-style crisis are already in place, the unwinding of eurodollar credit will be an additional, unexpected factor.

This will not necessarily be an easy crisis for investors to navigate. While a stampede of unseen elephants in the room looks increasingly likely to undermine the dollar fatally, past experience is that the initial reaction to a global crisis is usually to strengthen the dollar before it faces its true crisis. If this happens, it will be short lived because foreign owners of up to $135 trillion of dollar obligations both in the US and abroad are bound to turn sellers.

Introduction

The metaphor about an elephant in the room seems inadequate for describing the enormous, unseen emerging problems facing the fiat currency regime. The detachment of credit from real money, the insolvency of central bank balance sheets, the determination of commercial banks to withdraw credit when desperate borrowers need it most, the crisis spawned by rising interest rates, the collapsing of financial values due to rising bond yields, the challenge to the dollar-based regime from the two powerful Asian hegemons, and the challenge to capitalism from internal moral degradation. Oh, and don’t forget all the commercial banks and their borrowers which will go bust from yet higher interest rates and bond yields. And there will be the challenges to spendthrift governments faced with soaring deficits which will be impossible to finance on a non-inflationary basis.

But there is one additional pachyderm which has escaped notice. And that is the mountain of unrecorded offshore dollar credit, known as eurodollars and eurobonds.

Why is this? Well, in our mad world of statistics, if there are no records for something it is presumed to not exist. In the Bank for International Settlements annual reports, there is no mention of eurodollars. Except in passing occasionally, the same is true for the IMF and World Bank. But Claudio Borio and colleagues at the Bank for International Settlements have made some estimates of bank and non-bank on and off balance sheet exposures outside the US to dollars, which are in effect eurodollars. But to him and his colleagues these are not eurodollars, because the term is not mentioned. They fit the definition, which is as follows:

A eurodollar is a dollar credit created independently from the US banking system by foreign banks.

These are eurodollars, created in exactly the same way as a US bank creates dollars by lending them into existence. Bank debt is customer deposits which balance loan creation. But these deposits are offshore, so they are not included in US money supply statistics. There are some $6.5 trillion in US bank deposits owned by foreigners, of which $1.25 trillion are in US branches of foreign banks. Eurodollars are in addition to these deposits.

The debts of non-banks are the sum of the counterpart of loans made by the banks and additional obligations made between them. These are otherwise referred to as shadow banks. Shadow banks are insurance companies, pension funds, investment funds, and all institutions in the financial sector operating without a banking licence. They do not deal in credit, which is the preserve of licenced banks, but they enter into credit obligations with the banks and one another. And then there is the eurodollar bond market, representing an additional mountain of credit.

The origins of eurodollars

If you approach a non-US bank for a dollar loan and they agree to lend dollars to you, the bank will simply create it as if it was lending in its own currency. On its balance sheet, the loan to you is recorded as an asset. This is balanced (in the bank’s books, but not necessarily reflected in the presentation of your account) by a matching deposit, or liability in favour of you as depositor. The bank can do this in any currency, so long as there is an efficient wholesale market and clearing system — both of which exist for the dollar internationally and independently from the US banking system, though balances can equally be obtained in New York as well.

It is commonly believed that the eurodollar market commenced in the early 1960s, but that refers to eurodollar bonds. These were the logical inovation from eurodollar deposits, which had existed since 1955, if not before. Eurobonds kicked off with a loan to the Belgian government in May 1963.

The origins of an offshore dollar market, by which we mean dollar deposits issued outside the American banking system and not reflected in correspondent bank accounts in New York, commenced in the post-war years when the US’s Regulation Q limited bank deposit interest to 1% on 30-day deposits, and 2 ½ % on 90-day deposits. But you could deposit dollars at a London banker and earn more interest than the Regulation Q limitation. This became an entirely offshore market in London because UK exchange controls introduced in 1957 effectively prohibited them from borrowing and depositing dollars.

Demand for offshore deposits in London naturally led to innovation, with the Midland Bank leading the way. Midland had bid up to 1.825 % interest for 30-day deposits denominated in US$. This was 0.825% more than the maximum payable in the U.S. under Regulation Q. Midland then sold these dollars spot for sterling and bought them back forward at a premium of 2.125%. The resultant sterling therefore cost Midland 4% at a time when Bank Rate was 4.5%.[i]

Even though this challenged the gentlemen’s agreement between the Bank of England and the joint stock banks that set relationships at that time, Midland Bank’s dealing was initially tolerated by the Bank of England, probably because the currency inflows which were converted into sterling assisted the balance of payments. And by 1963, UK banks had accumulated over $3 billion in these eurodollar deposits. Furthermore, other European centres became active in this market, notably Italy, Switzerland, and France. And Japan was also creating eurodollar deposits. The market was not restricted to dollars: deposits were also being created in other currencies, adding an additional 15% or so to the total market.

There can be no doubt that the early years of the eurodollar market were fuelled by the post-Bretton Woods circulation of the dollar outside America, given impetus by the Korean war (1950—1953) and the Vietnam war (1955—1975). The accumulation of dollars in foreign hands led to the establishment and failure of the London gold pool. But it wasn’t just balances held by foreigners in the US banking system, but the accumulation of dollar deposits offshore which were being encashed for bullion.

Quantifying the current eurodollar market

Borio’s paper is not so much about quantifying the size of the eurodollar market, but the inherent risks in offshore dollar credit, which is why shadow banks are included in his paper. His calculations, which are based solely on currency obligations, are summarised in Table 1 below.

It should be noted that bank balance sheet dollar debts originated outside the US are liabilities with the same status as a customer’s bank deposit irrespective of where the customer is located. And other than onerous tax reporting regulations, there is nothing to stop an offshore bank offering deposit facilities to a US resident.

If eurodollar bank deposits were included in US money supply, there would be an additional $15 trillion added to it, being Borio’s estimate of on balance sheet debt of banks headquartered outside the US. And as noted above, US subsidiary branches of these banks are already covered in domestic money supply statistics. The off-balance sheet debt of banks headquartered outside the US is comprised mainly of credit obligations from currency swaps and commitments, an estimated 88% of which have the dollar on one leg. And the majority of these commitments are short-term. The other 12% represents payments in currencies foreign to the banks involved, such as euros, sterling, yen, and yuan where the other leg is not dollars.

From Table 1, we can see that the extra $15 trillion of eurodollar credit created by banks headquartered outside the US supports an immense structure of credit around which global business activity revolves. As the BIS article puts it:

“Embedded in the foreign exchange (FX) market is huge, unseen dollar borrowing. In an FX swap, for instance, a Dutch pension fund or Japanese insurer borrows dollars and lends euro or yen in the “spot leg”, and later repays the dollars and receives euro or yen in the “forward leg”. Thus, an FX swap, along with its close cousin, a currency swap, resembles a repurchase agreement, or repo, with a currency rather than a security as “collateral”. Unlike repo, the payment obligations from these instruments are recorded off-balance sheet, in a blind spot. The $80 trillion-plus in outstanding obligations to pay US dollars in FX swaps/forwards and currency swaps, mostly very short-term, exceeds the stocks of dollar Treasury bills, repo and commercial paper combined. The churn of deals approached $5 trillion per day in April 2022, two thirds of daily global FX turnover.”

FX markets are the correct area on which to focus, because as well as speculative flows, they represent payments for commodities, imports and exports, and all other cross-border transfers. As an example, let us assume a Chinese manufacturer wants to buy copper from Indonesia. Assuming the seller wants to be paid in dollars, the manufacturer’s bank will make the dollars available, debiting the manufacturer’s renminbi account at the current exchange rate. The bank can cover its dollar payment in wholesale markets, possibly from another Chinese bank because the Chinese banks will tend to be long of US dollars. Alternatively, there may be an Indonesian bank willing to sell it dollars. The point is that there are the ready means for the bank to cover the dollars paid to the Indonesian seller, without resorting to dealing with a US bank.

Foreign governments and their agencies in particular can be reluctant to involve American banks because beneficial ownership of US bank deposits is available to US government agencies. This is one reason fuelling the expansion of the eurodollar market. It was for this reason that in the 1960s the Moscow Narodny Bank was an active participant in the eurodollar market in London.

Potential risks

Much has been written about systemic risks, on the basis that a crisis in one banking system is likely to undermine the credibility of another. The common approach is to contain counterparty risks between centres as much as possible. And, indeed, this has been achieved in currency dealings following the failure of the Herstatt Bank in 1974. In that crisis, it was the time difference between Frankfurt and New York that led to settlement failures. That settlement risk was finally eliminated in 2002, when the Continuous Linked Settlement system was introduced. But that only applies to interbank transactions.

The continuous linked settlement system does not apply to continuing credit obligations, such as currency swaps and forward transactions, which as we can see from Borio’s analysis amount to $93 trillion. These are risks which may or may not be settled in future. The risks lie between bank customers in the shadow banking category (including the banks’ own off-balance sheet activities) and individual banks. As well as a banking risk, this market represents a currency risk as well.

Now that banks are restricting their balance sheet activities, we must allow for the contraction of the $93 trillion eurodollar market figure and the potential volatility in exchange rates it may cause. From the US Treasury’s TIC figures, we know that foreign interests own onshore US dollar deposit balances and financial assets are enormous amounting to $32 trillion, of which $7.25 trillion is in bank deposits, T-bills, and other short-term assets. With eurodollar credit, that’s a total of $125 trillion in dollar obligations. According to Borio, short-term eurodollar obligations amount to four-fifths of the $93 trillion total ($74.5 trillion), which added to onshore short-term obligations of $7.25 trillion gives a combined total of $81.75 trillion. This dollar liquidity is an enormous unseen elephant, which if it moves has the potential to crush its surroundings.

In addition, long-term credit obligations in the form of eurobonds are an additional $10 trillion, the substantial majority of which are dollar-denominated.

The fragility of foreign banking systems

Having quantified the market, we now turn our attention to its institutions. Eurodollars are dollar obligations created by non-US banks, including US bank subsidiaries located outside the US. The dollar balances in these banks support an enormous structure of credit, about 80% of which matures in one year, and therefore must be regarded as equivalent to cash (actual deposits) and near-cash (currency swaps and forwards). Ultimately, that is $74 trillion out of the $93 trillion total. This raises the question about the ability of their customers to pay the banks’ involved.

The eurodollar business is concentrated in the larger banks, the global systemically important banks, or GSIBs. Their share prices have rallied recently, in some jurisdiction more than others depending on the market’s reading of the short-term benefits of the ending of interest rate suppression. Importantly, their valuation incorporates a belief that interest rates will ease in 2024, reducing the pressure on their own balance sheets from falling bond values, collateral values, and a reduction in the prospect of non-performing loans.

However, there is a big question over this Panglossian view. Energy prices are rising strongly, and the banks themselves are drawing in their credit horns, putting pressure on interest rates to rise further, and therefore bond yields as well. And all this is on the eve of an almost certain slowdown in economic activity. Something will have to give.

Now put yourself in the position of, say, a Eurozone GSIB. The market has little confidence in your bank, rating it at a substantial discount to book value. On paper, your balance sheet leverage is twenty times assets to equity. These simple statistics tell you that your bank is at risk of a market run on it, given the reality expressed in the previous paragraph. The depositors are not the problem, it is your relationship with other banks in the wholesale markets. Clearly, you must not only de-risk your balance sheet if you haven’t already, but you must reduce its size.

You render your profits in euros, but you have liabilities in eurodollars. It is clear where the reductions in exposure should come from. It’s not just a question of eliminating currency risk, but the political pressures from your own government are to not reduce credit in the domestic economy. Therefore, you must sell dollars, reducing your presence in forex markets.

The other side of Triffin

Robert Triffin is famous for his explanation of why a country must manage its economy irresponsibly if it is to supply sufficient currency into international markets for it to act as a reserve currency. And this is precisely what successive US governments have done in the post-war years, accelerated after President Nixon suspended the Bretton Woods Agreement. The result has been an accumulation of dollar credit liabilities to foreigners, evidenced as deposits in US banks, government and corporate bonds, and portfolio investments in US equities.

When Triffin testified before Congress in 1958, he was either being simplistic for the benefit of politicians, or ignorant about the true role of credit. Even at that time foreign banks, predominantly in London, were dealing in dollar credit creating loans and deposits in addition to the dollar credit circulating in the US. If he had known this at the time, Triffin would not have had to argue so forcibly that to create the status of a reserve currency, the US government would have to follow irresponsible economic policies. However, when he became aware of dollar credit creation outside the US, he adopted the line I’m taking in this article. This is an extract from a BIS paper by Micheal Bordo (2017):

“Triffin did not take into account what became a substantial stock of US dollars held by foreign central banks offshore that made the US position worse according to his analysis. Years later, the growth of the offshore dollar market led Triffin to add official eurodollar deposits to dollar reserves held in the United States, an addition subsequently neglected by international economists. This point is not just an historical footnote.

“The point is worth elaboration because the same misapprehension that all dollars are held Stateside afflicts the more recent versions of Triffin. Four years after gold and the dollar crisis appeared, the world learned of a stock of $4.45 billion of dollar bank liabilities outside the United States as of September 1963 (BIS, 1964). Then, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) upped its estimate to $6.94 billion (BIS (1965). Central banks held about half of such offshore dollar deposits (BIS (1966, pp 146-147)), ‘presumably to obtain higher earnings on these funds’ than in the United States (BIS 1964, p 132).”[ii]

However, as one might expect and despite Triffin’s warnings, the US Government embraced the excuse to run trade deficits, and its near-twin budget deficits. This triggered the second part of Triffin’s dilemma, and that is these irresponsible economic policies were unsustainable and would lead to a crisis, such as occurred in 1931 and 1933. And that, as was argued by Felix Mylarski in 1929 would lead to a run against US gold reserves four years later, when Roosevelt reneged on gold convertibility for dollars in 1933.

Despite this history, the expansion of dollars in foreign hands, recognised in the US banking system and in the developing Eurodollar market, led to a further crisis in the 1960s — again, there was a run against US gold reserves. Initially, the Americans roped in the Europeans to commit their own gold reserves to suppressing the gold price at $35 in the London gold pool, which was established in 1961. But after a time, in 1967 that failed when sterling was devalued and France pulled out of the gold pool.

Today, it is hard to argue against another Triffin event being in the wings. This time, it is perhaps less obvious, because almost no one thinks that its reflection is in a rising dollar price for gold (which more accurately is a fall in the value of dollar credit). But it does matter. Just as a Triffin crisis has always been reflected in the dollar/gold relationship, it still is today, and it doesn’t need the breaking of an official gold standard to mark the event.

Debt deflation

In this article, I have demonstrated that there is a whole world of dollar credit additional to that recorded in the US banking system. It makes the dollar considerably more vulnerable to a “Triffin event” than generally realised, even by the increasing number of senior commentators who can now see that market expectations of declining interest rates later next year are a vanishing prospect.

There is the increasingly obvious pressure on CPI prices to rise from higher oil prices and a looming shortage of heating oil and diesel in the coming winter. There is adding evidence of somewhat vague theories, that the era of financially-driven currencies will give way to currencies associated with commodities, such as that proposed by Zoltan Posar’s Bretton Woods 3. But as has always been the case, the mainstream underestimates the economic consequences of the cycle of bank credit.

This cycle, which is responsible for the booms and busts evident in economies ever since the development of modern banking has been given added impetus from zero and negative interest rates. It is no accident that the banking systems which have the greatest leverage are those whose margins were compressed most by negative interest rates. Credit Suisse has already failed. Its GSIB peers in the Eurozone and Japan have been caught out with excessive balance sheet leverages and have now become risk averse, being fully aware of the twin dangers of falling bond values (to which some of them have excessive duration risk) and rising bad debts from businesses which could justify their debt levels at negligible interest rates, but not in this higher interest rate environment.

In short, this is why bank lending in the US, EU, and the UK is contracting. The Keynesians call this debt deflation, and their response is to recommend monetary expansion at the central bank level fuelled by an increase in the budget deficit to offset it. Alternatively, they suggest that policies leading to a decline in the exchange rate will stimulate consumer demand. Not only does this misdiagnose the problem, but in the context of Triffin it only serves to bring on the crisis.

Debt deflation can be split into two phases. The initial phase is a refusal by banks to extend credit because they are de-risking their own balance sheets. Inevitably, it occurs at the same time as demand for credit increases, leading to less credit and higher borrowing costs. This used to be described as a credit crunch.

The second phase is an acceleration of bankruptcies in small and medium size businesses (SMEs), the businesses which make up a Pareto 80% of any economy but are on no one’s radar, except that of lending bankers. Arguably, this phase is now kicking off, causing further caution for over-leveraged banks, forcing them to constrict their lending even more. The response of the authorities can be guessed at: accelerate the expansion of central bank credit in a vain attempt to stabilise the situation. But that has consequences for the currency.

The outcome is almost guaranteed

The planners’ assumption is that falling consumer demand will lead to lower prices. But to the extent that the authorities believe this is true merely exposes the levels of their economic ignorance, because output of production declines first and then consumption reduces as employees are laid off. Far from reflecting a decline in consumption, instead the purchasing power of central bank credit, or its base money, is undermined by a combination of its expansion and loss of faith in it by foreign holders.

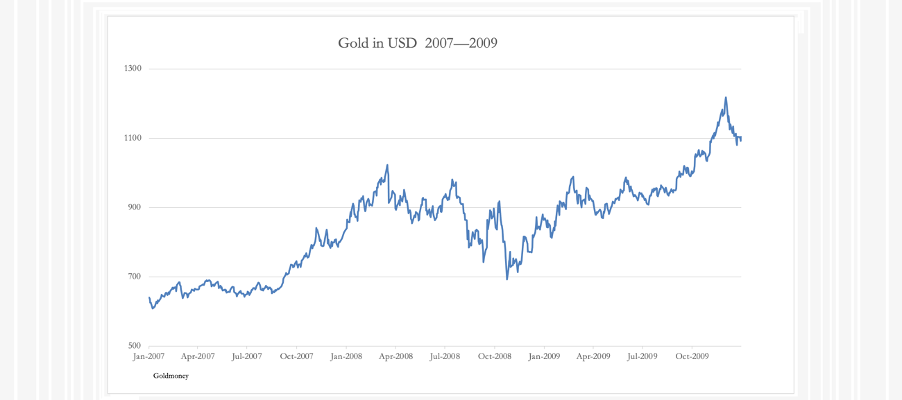

In the case of the dollar, this may not be initially true. When financial markets awaken to the prospect of higher interest rates and lower bond yields, their initial assessment is usually to fly to the supposed safety of the dollar from lesser currencies. We certainly saw this at the time of the Lehman crisis, reflected in the chart below of gold priced in dollars.

In the run up to the crisis, the gold price rose to $1023 in March 2008. The crisis then began to evolve, leading to the Lehman failure on 15 September 2008. The week before the event, gold was trading at $742, a fall of 27% from the March high. And after a brief rally on the news, it subsequently fell back to $692 on 24 October, before rallying to new highs against the dollar.

There are many other examples of an initial flight to the supposed safety of the dollar in a crisis, so much so that we should expect it as the contractionary phase of the bank credit cycle progresses.

The outcome, however, will bring all those elephants unnoticed in the room to life. Interest rates and bond yields will probably rise first, which appears to be already happening as illustrated below.

Furthermore, yields on bonds issued by many other governments are challenging new 5-year highs, so these are not isolated cases. Further increases in bond yields will crash bond and stockmarkets and undoubtedly lead to bank failures, probably in the Eurozone first because the Fed is already bailing out banks suffering from mark-to-market bond losses.

With rising bond yields and falling stock markets, global sentiment can be expected to rapidly turn bearish. Instead of ignoring it, market participants will almost certainly view the parlous state of central bank balance sheets and their further deterioration extremely negatively, while at the moment this is not being taken seriously. Government finances will then be taken to be a serious problem, not only undermined by rising interest rates, but an unwillingness of foreigners to recycle capital flows into government stocks. This will hit both the US and UK particularly hard, forcing up government borrowing costs substantially.

This is where all the previously unseen elephants in the room begin mounting a combined charge against the status quo. The common element of their attack will be fiat currencies, led by the dollar. Foreign holders of US securities will face massive losses on their $32 trillion invested, including $7.5 trillion in deposits and short-term bills. To this must be added the accumulated Eurodollars, a further $15 trillion of bank liabilities, a further $78 trillion of mostly short-term off balance sheet positions., and the $10 trillion of long-term eurobonds. That’s $135 trillion asking to be liquidated.

[i] See The Origins of the Eurodollar Market in London: 1955–1963, by Catherine Schenk, Academic Press, 1998.

[ii] BIS Working Paper 684: Triffin: dilemma or myth?

Buka akaun dagangan patuh syariah anda di Weltrade.

Source link