How Debt Jubilees Work

With debts at record levels around the world, there are folks calling for debt jubilees- the cancellations of certain types of debt.

After a period of stabilization, the Congressional Budget Office expects federal debt-to-GDP to eventually reach 200% while deficits structurally continue to grow as a share of GDP:

Chart Source: CBO

Importantly, the CBO always assumes there will be no recessions within their multi-decade forward forecasts. Since recessions do inevitably happen and result in less tax revenue and increased expenditures when they do, the CBO has had a historical tendency to understate deficit and debt growth.

Other developed countries are in similar shape. Most of them don’t have fiscal deficits as a percentage of GDP quite as large as the United States, but some of them have even higher debt-to-GDP levels due to sluggish GDP growth.

My prior article discussed the national debt and at what levels it becomes a problem. This follow-up article explores the concept of debt forgiveness including some of the nuts and bolts for how it can happen in certain ways, and how it can’t realistically happen in other ways.

Debt Jubilees: a 4,000+ Year History

In ancient times, debts were often about crop harvest outcomes. Farmers would rack up tabs with various counterparties throughout the year and pay them off at harvest season, but if the harvest failed for one reason or another, the farmers would be financially destroyed. When they were unable to pay their debts, they would generally lose their land to their creditors, and if that didn’t cover it, they might be forced into slavery to their creditors for a period of time.

If that happens enough times to enough people, it eventually becomes destabilizing at the whole societal level rather than just the individual level. More and more people end up as landless slaves, and wealth concentrates more and more into the hands of the few. The numbers get very lopsided, and eventually those with nothing to lose, and who greatly outnumber their masters, resort to violent revolution. No king wants to be in power when that happens.

So, kings would often use decrees to forgive certain types of debt and servitude, restoring freedom or land and resetting things for another several decades. Or they would put limits on how many years someone could be a debt slave until they are freed, even if their time in slavery doesn’t fully cover their debts.

Debt jubilees date back at least 4,000 years to ancient Sumer, Babylon, and other areas of western Asia. Ancient kings would sometimes forgive societal debts as a matter of public stability, and some of them put the practice into law at regular intervals or triggered by certain catalysts.

Ancient Israelites had the concept of a debt jubilee every five decades, where people could come out of servitude, return to their land, and so forth.

Solon, who is credited for building some of the foundations of ancient Greek democracy in the sixth century BC, used a partial debt jubilee as part of his solution to avoid catastrophic class conflict:

In the Athens of 594 B.C., according to Plutarch, ‘the disparity of fortune between the rich and the poor had reached its height, so that the city seemed to be in a dangerous condition, and no other means for freeing it from disturbances seemed possible but despotic power.’ The poor, finding their status worsened with each year- the government in the hands of their masters, and the corrupt courts deciding every issue against them- began to talk of violent revolt. The rich, angry at the challenge to their property, prepared to defend themselves by force. Good sense prevailed; moderate elements secured the election of Solon, a businessman of aristocratic lineage, to the supreme archonship. He devalued the currency, thereby easing the burden of all debtors (although he himself was a creditor); he reduced all personal debts, and ended imprisonment for debt; he cancelled arrears for taxes and mortgage interest, he established a graduated income tax that made the rich pay at a rate twelve times that required of the poor; he reorganized the courts on a more popular basis; he arranged that the sons of those who had died in war for Athens should be brought up and educated at the government’s expense. The rich protested that his measures were outright confiscation; the radicals complained that he had not redivided the land; but within a generation almost all agreed that his reforms had saved Athens from revolution.

–The Lessons of History, Will and Ariel Durant, 1968

It wasn’t necessarily out of kindness that rulers did this (although a significant subset of them aged well in history and were wise); it was basically just a solution to a societal math problem. It’s like if you run a computer long enough, eventually it starts to work less efficiently, as memory leaks and other issues build up. it starts to freeze and slowdown, frustratingly. It’s a mildly unstable system in other words. Refreshing the power and rebooting the system gets the computer running smoothly again.

Debt jubilees generally served that purpose; an occasional reset to wipe out some of the growing instabilities from prior generations, and begin with a cleaner slate and a renewed social contract. Otherwise these societal imbalances tend to cleanse themselves with more violent revolutions, with the many poor vs the few rich.

The Long-Term Debt Cycle

The modern version of this debt jubilee phenomenon has been the long-term debt cycle.

I described the long-term debt cycle in my September 2020 public article and my March 2021 newsletter, but I’ll provide a brief summary here now that we’ve seen more of it play out so far in this cycle.

We are all familiar with the 5-10 year credit cycle, where debt builds up in the economy and then gets partially cleared away by bankruptcies during recessions. However, each cycle ends up with higher debt/GDP ratios and lower interest rates than the prior cycle, due to central bank intervention.

Chart Source: St. Louis Fed

These lower rates allow for more debt accumulation (because the cost of servicing it is lower), but when interest rates run into zero or even slightly below zero, there’s really nowhere else to go. See how much private debt (orange line) builds up over decades and then runs into major headwinds when interest rates have hit zero:

With interest rates at around zero, and private debts so incredibly high, things start to crumble. However, unlike a normal business cycle, policymakers can’t just let this amount of indebted entities go bankrupt, because it would bankrupt the entire system at this level. The debt is simply too large relative to the money supply, and the economy would become revealed as basically a massive credit-fueled Ponzi scheme. Debts only could get this high in the first place due to central bank intervention, and now they are well above any natural clearing cycle. It becomes an existential problem for the country. If debt were allowed to simply default from that magnitude, the majority of the banking system would become insolvent, rather than only the weaker ones. There would be mass default by homeowners and corporations at scales that are likely to spark a revolution.

An analogy I originally saw from Nassim Taleb comparing business cycles to forest fires can be adapted here to apply to the long-term debt cycle.

A normal forest fire is environmentally healthy even though it causes suffering, because it clears out all of the excess and allows for renewed growth. Invasive plant species are killed, excess dead/dry material is burned away, while fire-resistant species that have been through this before can rebuild, and soil and roots often make it through. The ecosystem gets renewed.

However, if people prevent forest fires multiple times in a row, and let more and more dry material build up, then inevitably a forest fire occurs that is utterly massive, unstoppable, and environmentally destructive. It is so intense that it burns away not only the invasive species, but even fire-resistant species, and heavily damages the soil and root systems, leading to a far less healthy aftermath. Nothing good comes from a fire that intense. It only destroys.

So, when that massive private debt bubble starts to collapse with interest rates at zero, it’s like this massive inferno type of forest fire, and the government balance sheet is used to prevent it. Massive fiscal spending is done to prop up the solvency of people, corporations, and/or banks. If well-handled, it distributes relatively evenly through society. It poorly-handled, it can end up like socialism for the rich only, where banks get bailed out but homeowners do not.

After that, the government itself has too much debt to be maintained with positive inflation-adjusted interest rates. With such high debt levels relative to GDP and tax revenue, the government can only realistically service debt levels by holding interest rates below the prevailing inflation rate.

If the country is an emerging market and owes debt in a foreign currency, they generally have no choice but to default if the public debt becomes too problematic. If the country is a developed market and its liabilities are denominated in its own currency, the government instead massively increases the currency supply, holds interest rates below the inflation rate, and therefore “defaults” in purchasing power terms without actually formally defaulting. Bondholders get paid back at the terms of the loan but with devalued currency.

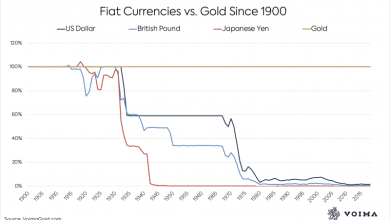

My view for a couple years now is that much of the developed world is in a currency devaluation process. Interest rates will be spending the majority of time below the prevailing inflation rate, meaning that cash and bonds will lose purchasing power over time.

This chart shows the Fed Funds rate vs year-over-year CPI, and we can see that ever since the global financial crisis in 2008 and then especially since the pandemic, there has been a big disconnect between the Fed Funds rate and the rate of CPI growth.

Private-to-Public Debt Conversion

As described in the prior section, debt jubilees go from bottom to top in the debt hierarchy.

The private sector gets partially bailed out in one way or another, and this debt gets pushed up to the government level, where it then gets repressed and devalued.

For example, student loans can be forgiven by the government, corporations can be bailed out with cash injections, households can be bailed out with cash injections, banks can be bailed out with troubled asset relief programs, and so forth. And when all of that winds up on the government balance sheet instead, it gets inflated away by the central bank holding interest rates persistently below the inflation rate. Holders of currency and holders of bonds are the final payers of the bill.

The Japan Example

Japan was an interesting example of this in a more low-key sense. They had an absolute massive equity, real estate, and debt bubble in the late 1980s and early 1990s, from which in many ways they have still never fully recovered. Around the same time, their demographics stalled, meaning the population stopped growing and became far older on average. In the three decades since then, Japan’s balance sheet has undergone a massive transformation.

First of all, they have had an unprecedented rise in government debt to GDP from under 75% in the mid-1990s to 266% today.

Chart Source: Trading Economics

The government continually taxed less than it spent, averaging about 5% fiscal deficits per year. Importantly, rather than spending that on things like foreign military expansion and waste, it was spent domestically on the people. Japan has among the lowest levels of wealth concentration in the world, and rather low levels of political polarization and populism because of that.

Secondly, they began a set of policies known as “Abeconomics” in 2012 under Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. The focus was on three things: aggressive monetary easing by the Bank of Japan, substantial ongoing fiscal stimulus, and corporate reform towards more results-oriented management.

We can see the rapid change in the size of the Bank of Japan’s balance sheet starting in late 2012, which also coincided with a decade-long bull market in Japanese equities:

However, Japanese corporate balance sheets strengthened significantly since then. Horizon Kinetics has been doing great research on this over the years and this chart from them shows that Japanese corporate net debt/EBITDA went from over 5x in 2012 to a little above zero in 2019:

Chart Source: Horizon Kinetics

It’s hard to overstate how big of a transformation that was. 5x net debt/EBITDA for the index as a whole is a rather high leverage ratio. Having near zero net debt/EBITDA means that corporations have almost as much cash as debt on their balance sheets, which means they have remarkably strong balance sheets. This was a massive corporate deleveraging, but it’s almost invisible if you look at the wrong metrics, such as looking at debt levels without considering cash levels. Their absolute debts are still high and only cooled off a bit, but the amount of cash on their balance sheets has grown considerably.

Japan has been the exception to the general rule; usually this private-to-public deleveraging is a very inflationary process but Japan managed to do it for decades without almost any price inflation, and with very low monetary inflation. They have had among the slowest money supply growth because a large part of the fiscal expansion at the government level (which increases the money supply) was offset by reductions in corporate credit (which reduces the money supply). In back-of-the-envelope math terms, Japan’s government has been increasing the broad money supply by about 5% per year for a long time, while the private sector has been reducing it at about 2% per year, resulting in only 3% net annual broad money supply growth on average over the past two decades.

Why This Isn’t Easily Repeatable

In my view, too many macro analysts look at this and assume the rest of the world will have the same result as Japan. It’s like a de-facto assumption among analysts that this is just how things will go, because global demographics will do the same as Japan. However, Japan has a structural current account surplus, positive net international investment position, low wealth concentration, and higher-than-average societal harmony.

Europe can do this, but they have to navigate Eurozone politics while doing it. Germany and Italy don’t exactly see economic policy the same way, for example. China can do this, but is facing its demographics cliff at a much lower level of economic development per capita than Japan did and China is more of an authoritarian regime than Japan, so it’s not an apples-to-apples comparison.

The United States is the opposite of Japan in many ways; the country has a structural current account deficit, deeply negative net international investment position, the highest wealth concentration in the developed world, and below-average societal harmony. The United States’ likelihood of repeating the Japan playbook without having more drama along the way is quite unlikely.

And importantly, Japan did this during a decade of global deflation; commodity prices were in a structural bear market from 2008 to 2020. The US completely reversed its declining energy production with shale oil during the 2010s, which upended the global energy industry with a big supply/demand imbalance for a while, resulting in excess supply and low prices.

Abundant oil and gas, combined with slowing Chinese economic growth, made for rather low commodity prices across the board. Japan, as a net commodity importer, had near-perfect disinflationary conditions to benefit from during their balance sheet transformation.

Here is US oil production. Japan’s 2012-2019 corporate deleveraging occurred during that huge increase in US oil output, which was a massive deflationary gift to the world while it lasted, and which won’t be repeated:

And here is the CRB index, which represents the price of a basket of commodities. Japan’s 2012-2019 corporate deleveraging occurred during that massive decline in commodity prices:

In other words, Japan did this from a stronger-than-normal financial position, and did it during a particularly disinflationary decade in the global economy.

It’s a mistake to assume that other countries trying to do this during a decade of supply/demand commodity tightness, or that are starting from a point of having structural current account deficits, will be able to do this as smoothly as Japan. For many, it will probably be a much more inflationary situation. Even for Japan going forward, I think it could be a more inflationary situation.

The US Example

This chart shows household and corporate debt in the United States in absolute terms, as a percentage of GDP, and as a percentage of money supply.

Chart Source: St. Louis Fed

And here are the same house hold and corporate debt charts, but with the monetary base in blue:

Chart Source: St. Louis Fed

We can see how much changed since the Global Financial Crisis, which is when interest rates hit zero. The total amount of debt dipped a bit and then went up slowly, but went down dramatically as a percentage of GDP and money supply, as the monetary base expanded dramatically. In other words, rather than letting the numerator (debt) crash too much, it was the denominator (the amount of various types of monies, including base money and broad money) that was substantially increased.

At first this was not inflationary for consumer prices (it was during that decade-long period of commodity oversupply), but as time went on and as commodity markets became more tight in the post-pandemic world, it became inflationary.

Meanwhile the US, unlike Japan, has a massive structural trade deficit:

Chart Source: Trading Economics

And a deeply negative net international investment position:

This gives the US a lot of vulnerability to global supply chain disruptions, and reliance on foreign capital inflows. Overall, it looks a lot like how the United Kingdom looked back in the 1940s, with a structural trade deficit, a weakened industrial base, and seeing competition from a rising economic power (which for the UK was the US back then, and for the US today is China).

Why Central Banks Can’t Outright Forgive Debt

The government can do various actions to reduce the private sector debt load. By running large deficits, they spend more money into the economy than they take out, which allows companies and individuals to strengthen their balance sheets at the expense of the government’s balance sheet getting worse.

This chart shows US federal debt and US corporate debt, as a percentage of GDP. We can see how they tend to move inversely, with the exception of the COVID-19 crash because GDP itself fluctuated wildly and corporations didn’t really deleverage:

Chart Source: St. Louis Fed

When governments get over 80% debt-to-GDP ratios, their central banks generally become the entities that buy the majority of the debt, and they do so via the ex nihilo creation of new base money.

This is because government debt eventually gets so big that it would start crowding out other assets. The debt would run into liquidity issues as there simply isn’t enough money in the private sector that wants to keep buying it at low rates. So, the central bank creates new money and buys the bonds with it.

Fiscal austerity (raising taxes, cutting spending, and thus reducing the fiscal deficit) is often tried at this point, but almost inevitably fails at this level. When private debts and public debts are so high, austerity results in slower GDP growth (and thus no reprieve in terms of the debt-to-GDP ratio) and rising levels of populism when it is attempted. Politicians that do austerity policies tend to get voted out of office when debts are this high and/or wealth concentration is high, and so in multiple ways it ends up not being a sustainable outcome to this situation. Austerity can work prior to a massive debt bubble accumulating to prevent it in the first place, but once that bubble is there, it’s too late.

At that point, the ship has sailed. The event horizon has been crossed. There is too much government debt relative to currency, and the debt itself cannot be massively reduced without systemic collapse. So, policymakers turn to the currency instead, and make a lot more of it. That’s what separates a long-term debt cycle from a normal business credit cycle. An expansion of the denominator itself is what alleviates it, rather than a reduction in the numerator, but that usually comes with major consequences including high price inflation.

A natural question people may ask is why can’t central banks just forgive the portion of the government debt that they hold? If the Bank of Japan owns about half of Japan’s government debt for example, can’t they just forgive that, and therefore cut Japan’s government debt in half without affecting any private entity? Couldn’t the government sector, after having bailed out the private sector, have its debt forgiven by its own government-controlled central bank?

Well, yes and no. Mostly no. Here’s why.

Central banks have assets and liabilities. Their assets consist of government bonds and then perhaps other types of assets like mortgage-backed securities, corporate bonds, or even equities. Their liabilities primarily consist of currency in circulation and commercial bank reserves. In other words, if you own some paper currency, that is a liability of your central bank. And commercial banks store their cash at the central bank, and that cash represents a liability of the central bank.

Basically, we can say that the monetary base (currency in circulation and bank reserves) is collateralized by government bonds and other assets on the central bank balance sheet.

The Federal Reserve’s balance sheet is as follows:

Chart Source: Federal Reserve

Most governments that desire not to be “banana republics” maintain some degree of separation between the government and the central bank. The president or prime minster of a country cannot just dictate central bank policy, in other words. This is because this level of control would be too prone to manipulation. The president could cut interest rates and perform quantitative easing six months before his election to give himself the best odds of re-election, for example, even if it’s not what the economy needs at the moment.

Fiat currency is a game of confidence. It’s not backed by anything other than legal force and guardrails that create firm rules for how it can be issued and by whom. To break those rules is to risk breaking the currency. Everything is backed by something else and if you remove the backing, then there is nothing.

In practice, during government debt crises, this independence between the government and central bank weakens. The Federal Reserve was basically “captured” by the Treasury Department from 1942-1951 in order to fund the war and peg Treasury bonds below the inflation rate, for example. However, they still maintained some small amount of independence, including their own solvency, and eventually they were able to separate again with legal decree (the Treasury-Fed Accord).

Central bank independence only works if central banks are technically solvent. In other words, they need to hold more assets than liabilities. If they have more liabilities than assets, they are insolvent, and thus cannot realistically act independently. For central banks to be viewed as credibly independent, it requires them to be solvent.

Suppose, for example, that the Fed “forgives” half of the US federal debt that it holds in the form of a debt jubilee and just writes it off by saying, “you don’t have to repay us”.

As of this writing, the Fed has $8.878 trillion in assets, of which $5.731 trillion consists of Treasuries. It also has $8.837 trillion in liabilities, which mostly consist of physical currency and bank reserves. So, it has a little under $41 billion in capital, referring to the difference between assets and liabilities.

If the Fed were to just forgive half of the Treasuries, or $2.866 trillion worth of them, that would reduce the asset side of the Fed’s balance sheet by that amount, without affecting the liability side. They would have $6.012 trillion in assets, $8.837 trillion in liabilities, and thus be insolvent with -$2.825 in capital.

Would that affect anything overnight if they did that? Not necessarily, no. Some central banks have had slightly negative capital before; it’s not as though the world stops spinning if that happens. This is what makes central banks different than commercial banks.

However, if the central bank has trillions of dollars in negative capital, it is no longer independent, because it is no longer solvent. It has no real authority to do anything independently at that point, all illusions of independence are gone, and it is entirely reliant on the government for its solvency. The whole idea of how money works in the modern fiat currency system ceases to make sense at that point.

Older financial systems used to have gold at the base and paper currency on top, supported by that gold. Modern fiat currency systems are instead rather circular. Commercial banks store their cash at the central bank, which are assets for the commercial banks and liabilities for the central bank. In turn, the central bank holds government debt as its primary collateral assets. Government debt is backed up by the government’s ability to tax its citizens, and in practice, by having the central bank create new bank reserves to buy its government debt when needed.

We can’t just remove one piece of it, like government debt from the central bank balance sheet. The monetary base is collateralized by government debt, and government debt is supported by expanding the monetary base when needed. It’s basically an ouroboros.

How Central Banks Can “Kind of” Forgive Debt

As the prior section covered, central banks can’t just outright forgive government debt without having trillions of dollars worth of negative capital and losing any semblance of central bank solvency and independence.

However, governments and central banks can do an accounting sleight of hand instead, if they work together. The 1930s dollar devaluating against gold provided a historical example.

On the evening of April 18 (1933), FDR gathered his economic advisers in the Red Room at the White House to discuss preparations for the forthcoming World Economic Conference in London. With a chuckle, Roosevelt casually turned to his aides and said “Congratulate me. We are off the gold standard.” Displaying the Thomas amendment to the Agricultural Adjustment Act, which gave the president the authority to devalue the USD against gold by up to 50% and to issue $3B in greenbacks without gold backing, he announced that he had agreed to support the measure.

-Lords of Finance, Liaquat Ahamed, 2009

In 1934, the Gold Reserve Act, passed by Congress and the President, required the Fed to give its gold to the Treasury. In order to avoid rendering the Fed insolvent with that action (by giving over a large portion of their asset base in exchange for nothing), the Treasury also gave the Fed an equal amount of gold certificates that equaled the value of the gold they were handing over to the Treasury.

The gold certificates theoretically represent a claim to the gold, but in this case are non-redeemable, and thus don’t really mean anything. Giving the Fed those gold certificates was like giving a kid a plastic toy steering wheel to play with in the back seat while the parent drives the car. But from a legal accounting perspective, those gold certificates kept the Fed solvent by avoiding any reduction in official value from the asset side of their balance sheet, and have been held by the Fed for almost 90 years.

In fact, inflation and interest payments eventually grew the Fed’s balance sheet so large in nominal terms, that they don’t even need those gold certificates to be solvent anymore, since their capital would still be positive if those gold certificates were deleted. The Fed has $11 billion worth of gold certificates and $41 billion worth of capital, so they technically don’t even need those certificates anymore, but for most of the period since 1934, those now-meaningless certificates were a key part of what made the Fed’s balance sheet technically solvent. It sounds tiny now, but $11 billion used to be a massively important part of the Fed’s assets, and those gold certificates were a key part of the Fed’s accounting solvency. When they were given to the Fed, they constituted the vast majority of the Fed’s assets at the time.

The modern extension of this can mean that a central bank can do some debt restructuring with its government.

With agreement from the government, the central bank of a country could convert some or all of its government bond holdings into 100-year zero-coupon bonds, for example. It would be a unique type of bond, only held by the central bank.

That debt, for all intents and purposes, is no longer relevant. With a big chunk of government debt converted to non-interest bearing 100-year bonds, the central bank can now raise interest rates to positive real levels, above the inflation rate, and even if normal government bonds have their interest rates go up, it won’t affect those 100-year interest-free bonds. Those bonds are terrible investments, but they technically keep the central bank solvent in accounting terms if held to maturity, like the non-redeemable gold certificates did. I wouldn’t be surprised if governments turn to a solution kind of like that at some point. They can also technically re-value gold on their balance sheets relative to their fiat currencies.

The other way is more simple. The Federal Reserve can hold interest rates below the inflation rate for a prolonged period of time, let inflation run hot, and burn debt away. They lose a lot of credibility by doing that, but when debt is extremely high, that’s historically what tends to happen. It’s what made the 1940s (a high debt environment) very different than the 1970s (a low debt environment).

Chart Source: St. Louis Fed

Chart Source: St. Louis Fed

As I write this, Japan currently has a 2% inflation target, short-term interest rates at -0.1%, and yield curve control in place at 0.25% for the 10-year Japanese government bond. The way they can maintain this yield curve control is by being willing to create new bank reserves ex nihilo and buy an unlimited amount of bonds if bond yields try to go above 0.25%. However, there is no free lunch, and so when they control interest rates, it means they give up control of their exchange rate. As Reuters reports in that link:

TOKYO, Feb 10 (Reuters) – The Bank of Japan said on Thursday it would buy an unlimited amount of 10-year government bonds at 0.25%, underscoring its resolve to prevent rising global yields from pushing up domestic borrowing costs too much.

Suffice to say, my main plan throughout this period is to mainly hold scarce assets- things like productive cash-producing companies, commodities, real estate, and hard monies, rather than being too heavily invested in fiat currency or bonds at any given time other than for some liquidity and optionality.

Source link