Does the National Debt Matter?

Published: February 2022

This article examines the concept of sovereign government debt from an investment perspective and a social perspective.

What happens when it gets too high? And how high is too high?

For decades now, there have been many over-simplistic views on government debt. Some people were acting as though it would be a near-term catastrophe thirty years ago, and it never was. On the other hand, there are people who say it barely matters at all, ironically when it’s probably starting to actually matter.

As with most things in life, the truth is somewhat more nuanced. This article dives into some of the details as far as the available data are concerned.

How National Debt Works

Back in the “old days”, money was gold, and gold is physically scarce. Banks could take in gold deposits and issue paper claims against it.

Because carrying a lot of metal money around is risky and inconvenient and creating credit is attractive to both lenders and borrowers, credible parties arise that put the hard money in a safe place and issue paper claims on it. These parties came to be known as “banks” though they initially included all sorts of institutions that people trusted, such as temples in China. Soon people treat these paper “claims on money” as if they are money itself.

-Ray Dalio, The Changing World Order

Knowing that not all people would choose to withdraw their gold at once, the banks could issue more paper claims than the gold on deposit, invest some proceeds in longer-duration less-liquid assets, and begin what has basically been a multi-century-long game of musical chairs that has to keep running to not break. This is fractional reserve banking and it is used throughout the world.

Governments could also issue paper currency that their economies would use in everyday activities, and it was redeemable for a defined amount of gold, which is what gave the currency credibility. Like banks, governments didn’t need to have 100% gold deposits on hand, but had to maintain a credible percentage so that the public wouldn’t be spooked and try to perform a mass redemption. Due to this, if a government wanted to bring in income (gold), it needed to tax for it, borrow it, or force banks and people to deposit it in exchange for government-issued paper claims (currency) on it.

During the two world wars, all major currencies were devalued relative to gold. Governments printed a lot more currency than they had gold to back up, so they had periods where they suspended redemption of currency for gold, and then periods where it was redeemable but for a much smaller amount than before.

This can be considered a sovereign default, because if you were holding a paper dollar or a paper pound based on the promise that it was redeemable for a specific amount of gold, and then the government overnight said that it’s either not redeemable, or redeemable for less than before, then they unilaterally broke the contract while it was being used. People’s savings were drained for war.

In the late 1960s, the global money system started to break down again because more paper claims were issued than there was gold in government vaults, and so they defaulted on the system again. Since 1971, most countries have been on a fiat standard instead, meaning that their currency isn’t defined by, or redeemable for, anything. The government issues money, and people use that money. Throughout emerging markets, many of these fiat currencies have hyperinflated, but developed markets have been able to manage moderate inflation during that period, and keep their unbacked currencies in use.

In practice, inflation has been a lot more rapid since the shift towards modern central banking, and especially since 1971.

Chart Source: Ian Webster, annotated by Lyn Alden

However, even under this unbacked fiat currency framework, governments still bind themselves by old laws for how currency can be issued. Governments can’t just print as much currency as they want or issue as much debt as they want without certain legal constraints, meaning they have checks and balances. And this is pretty important, because these rules serve as guardrails to ensure that governments don’t turn into “banana republics” with no credibility by printing as much currency as they want. The rules keep fiat currencies from losing value at an even quicker pace than they already are.

For example, the US Treasury can print physical currency and coinage. The Federal Reserve, however, is the entity that distributes it. Paper dollars are technically a liability of the Federal Reserve, collateralized by (but not redeemable for) US government bonds, mortgage-backed securities, and gold. Most currency only exists on commercial bank ledgers, and is lent into existence by commercial banks that have to operate within the confines of capital ratios and profitability.

The President can’t simply spend as much money as he wants on behalf of the federal government; Congress has to approve all significant spending plans. When Congress and the President approve spending, the Treasury Department has to make sure they have enough money for it, which sounds ironic because they literally print currency. However, they are not allowed to simply print currency to cover their own spending decisions, because they still legally operate under old laws as though currency is scarce.

The US federal government brings in currency via taxes, and spends currency into the economy. Usually they run a fiscal deficit by spending more than they are taxing, and so they also have to issue government bonds, bills, and notes (debt) to bring in additional currency to cover that gap. Their total cumulative amount of debt outstanding is the national debt.

The most important metric is debt as a percentage of GDP, since it gives us some context for how large the debt is relative to the ability of the government to service the interest and principal of that debt.

My article on money printing goes into the mechanisms for how new money enters circulation. In short, broad money is created either when commercial banks make loans, or when the Federal Reserve creates new base money to buy assets from non-bank entities, or when the federal government (Congress and the President) run large deficits and have the Federal Reserve create new base money to buy that debt on the secondary market. Base money can be created unilaterally by the Federal Reserve, but it needs one of those three mechanisms to get into the broad money supply.

National Debt in a Separate Currency

We all understand that households and businesses are constrained by debt. If they have too much debt relative to their incoming cashflows, they can run into solvency problems and default on their debts, and thus go bankrupt.

Governments that don’t issue their own currency are similar in that regard. For example, local governments and state governments do not print currency; they get income from tax revenue and debt issuance, and they spend that back into their local economies. If they are unable to pay their bills, they have no way to print money for it, and can default and go bankrupt.

This is true for two types of national governments as well, who have foreign-currency debt liabilities.

1) Many emerging market countries do issue their own currency, but then also borrow foreign currencies from foreign creditors. For example, a government of a country in South America or Africa or southeast Asia might borrow dollars or euros, since foreign lenders don’t trust the credibility of their local currency. These governments can’t print dollars or euros, and so if for some reason their cash flows cannot cover their interest payments and principal payments, they can default and be forced to go through a restructuring/bankruptcy process. Emerging market sovereign debt defaults have unfortunately been rather common over the past several decades.

2) Some developed countries don’t control their own currency. Most notably, the Eurozone countries including Germany, France, Italy, Spain, and more than a dozen other European nations share the same euro currency. Their governments and central banks can’t issue their own currency units, and instead rely on supra-sovereign entities (e.g. the European Central Bank) to do so. These countries bring in currency from taxes and debt issuance, and if for some reason they cannot pay their debts, they are at risk of actual default and the associated restructuring that would come with that.

Back in 2012, many countries in southern Europe experienced the European sovereign debt crisis. Several countries including Italy, Portugal, Greece, and others reached sovereign debt levels that were over 100% of their GDPs. Lenders became spooked that these countries would be unable to support their debts with tax revenue, and started demanding higher interest rates to lend to them.

This problem quickly escalated because once the bond rates start increasing to high levels, the interest expense on such high debt loads becomes effectively unpayable, so it increases the chance of default. Since the chance of default is higher, lenders demand even higher bond rates to compensate for that risk, which further increases the chance of default. It becomes a vicious self-reinforcing cycle, nearly guaranteeing some sort of default and restructuring if left unchecked.

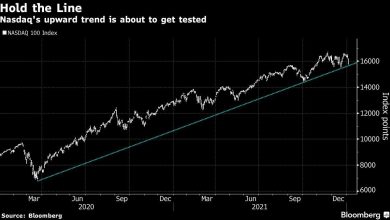

So, even though inflation was moderate in 2012, their bond rates soared. Here is the history of Portugal’s 10-year government bond rate, for example:

Chart Source: Trading Economics

However, eventually the European Central Bank stepped in. Mario Draghi, who was the president of the ECB at the time, said they would do “whatever it takes” to fix the problem. They printed hundreds of billions of new euros worth of base money within the year and used it to buy large portions of the bonds of these countries to drive down their bond rates and restore confidence that they would not default. In other words, they monetized the sovereign debt of several Eurozone countries, rather than letting their fiscal situations spiral out of control and default.

The same thing happened during the COVID-19 pandemic, except the ECB front-ran the problem and bought tons of debt before rates ever became questionable. Trillions of new euros in base money were created, and for several countries, the ECB was responsible for purchasing 100% of government bond issuance during the pandemic.

Italy, Portugal, and Greece now have higher debt-to-GDP ratios than during the 2012 European sovereign debt crisis. But because it is understood at the moment that the ECB will buy as many bonds as are necessary to keep the bond rates low, there is no crisis. However, their banking systems are sluggish, and savers are gradually losing purchasing power, because interest rates are artificially held below the prevailing inflation rate.

The summary for this section is that when debts are denominated in a currency that you cannot print, whether you are a household, business, local government, state government, or national government, debts can be realistically defaulted on.

When debts go above a certain percentage of income and become recognized as unserviceable, these entities either default and go through a bankruptcy/restructuring process, or become beholden to external creditors in order to remain solvent. Having high debt levels relative to GDP is therefore quite a serious problem.

These types of countries are also vulnerable to bank “bail ins”, like what happened to some European countries during this process. If the commercial banking system becomes overleveraged and starts to become insolvent, the nation’s government is unable to bail them out, because they cannot print new money themselves. If this happens, depositors in the bank can lose some of their savings, as the bank is forced to take some of the deposits and convert it to shareholder equity to avoid a complete insolvency meltdown.

However, things work quite differently if a national government issues its own currency and denominates most or all of its debt in its own currency.

National Debt in a Country’s Own Currency

Many major countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Japan, and China issue their own currency, and all or most of their sovereign debt is also issued in their own currency.

This makes the possibility of actual government default nearly impossible, because if push comes to shove, they can force their own central banks to print new base money and monetize the government bond issuance. Russia defaulted on government debt denominated in its own currency once, but that was a rare exception that they did by choice. Globally, such an event almost never happens.

However, government debt still matters, but in a different way. When debt levels start to get very high, their central banks start creating new base money to buy government bonds, either directly from the government or on the secondary market. This process is known a “debt monetization” and in the long run tends to lead to significant currency debasement.

Basically, when government debt as a percentage of GDP gets very high but is denominated in its own currency, rather than default in nominal terms, they “default” with inflation and financial repression. They hold interest rates low, have their central bank create new money to buy the bonds, and let inflation run high. Bondholders get paid back, but in weakened currency. As a result, bondholders lose purchasing power on their assets.

Here’s another look at more metrics:

This process negatively impacts holders of cash as well. Anyone holding cash deposits in commercial banks, or paper cash, or government bonds generally fails to keep up with inflation in this environment. They persistently lose purchasing power with their savings, because the supply of currency units is going up a lot faster than the supply of scarce goods and services.

I covered this concept of the long-term debt cycle back in 2020 and touched on it again in my May 2021 newsletter, and since then, the market has been surprised by price inflation running to over 7% while the Federal Reserve held rates at zero anyway. However, market participants that are familiar with this history have been less surprised by this outcome, since they realize that policymakers are boxed in by math.

For instance, M. Reinhart and M. Sbrancia published a working paper for the International Monetary Fund back in 2015 called The Liquidation of Government Debt that outlined much of the process that the developed world is now going through with deeply negative inflation-adjusted interest rates. And this was actually an updated of a 2011 paper that they wrote for NBER.

Here was the abstract of their 2015 IMF paper:

High public debt often produces the drama of default and restructuring. But debt is also reduced through financial repression, a tax on bondholders and savers via negative or belowmarket real interest rates. After WWII, capital controls and regulatory restrictions created a captive audience for government debt, limiting tax-base erosion. Financial repression is most successful in liquidating debt when accompanied by inflation. For the advanced economies, real interest rates were negative ½ of the time during 1945–1980. Average annual interest expense savings for a 12—country sample range from about 1 to 5 percent of GDP for the full 1945–1980 period. We suggest that, once again, financial repression may be part of the toolkit deployed to cope with the most recent surge in public debt in advanced economies.

In that IMF paper, they outlined three main tools of financial repression. The first is to hold interest rates below inflation, directly or indirectly. The second is to use regulation to force market participants to hold cash and bonds even if they lose money on them, by means of capital controls and banning alternative ways to protect capital. The third is to monetize the debt directly or indirectly with the central bank as needed.

It would do investors well to be familiar with these concepts. They were in use from the 1940s into the 1950s (and in some ways, continuing to the 1970s) in dozens of developed countries, and the debt levels are now in a similar position again, with signs that the same thing is happening all over again.

How Much National Debt is Too Much?

When a country starts getting to about 100% debt-to-GDP, the situation becomes nearly unrecoverable.

What I mean by “unrecoverable” is that there is a vanishingly small probability that the bonds will be able to avoid default and pay interest rates that are higher than the prevailing rate of inflation. In other words, those bonds will most likely begin to lose a meaningful amount of purchasing power for those creditors who lent money to those governments, one way or another.

And as such, any country that starts getting up close to 100% debt relative to GDP, starts having a lot of its debt bought by its own central bank (aka “debt monetization”), rather than all of the debt being bought by private creditors. The debt load get so large that they would begin to crowd out available liquidity, and they become increasingly likely to provide negative inflation-adjusted returns during their duration, and so the debts start being monetized by the central bank at that point.

This avoids crowding out the private sector, and avoids a fiscal spiral of higher and higher bond rates.

More specifically, a study by Hirschman Capital noted that out of 51 cases of govt debt breaking above 130% of GDP since 1800, 50 governments have defaulted. The only exception, so far, is Japan, which is the largest creditor nation in the world. By “defaulted”, Hirschman Capital included nominal default and major inflations where the bondholders failed to be paid back by a wide margin on an inflation-adjusted basis.

There’s no example I can find of a large country with more than 100% government debt-to-GDP where the central bank doesn’t own a significant chunk of that debt. Central banks quickly increase their holdings of government debt when the debt gets that large relative to the size of the economy.

Even the US Congressional Budget Office shows that the current forecast is dire, despite the fact that for political reasons they never factor recessions into their forecasts, and recessions result in larger deficits when they occur:

Chart Source: Congressional Budget Office

We can run some simple math with an example.

The United States has federal tax revenue equal to somewhere between 15% and 20% of GDP, and it has held that range rather consistently despite having a multitude of different tax policies over that time:

Chart Source: St. Louis Fed

When you add state and local tax revenue to the mix, total tax revenue is closer to 30% of GDP, and so the federal portion would have a tough time going much above 20%.

Let’s say that annual GDP is $25 trillion as it will be soon, and that federal debt is 130% of GDP, which would equal $32.5 trillion. If we assume that federal tax revenue is 17% of GDP, that’s $4.25 trillion per year in tax revenue.

So right off the bat, we can calculate that the debt/revenue ratio of the federal government in this example is $32.5 trillion divided by $4.25 trillion, or about 7.6x. If this were a company, it would be junk bond status based on that.

Texas Instruments (TXN), for example, has $7.7 billion in debt and about $17.6 billion in annual revenue, or about a 0.45x ratio of debt to revenue. That’s investment grade, although of course it depends on the profit margins of the company. Texas Instruments currently brings in about $7.3 billion in net income per year, so it has a debt/income ratio of 1.05x. If they devoted most of their net income to paying down debt, they could do so in a little over a year. Any lender can see that they have a good chance of being able to service their debt for the foreseeable future.

Federal spending is typically 20% to 25% of GDP per year (outside of major wars and crises). The US runs a structural fiscal deficit, which is how it built up so much debt since the 1970s. This chart shows federal government receipts in blue and federal government expenditures in red, both as a percentage of GDP:

Chart Source: St. Louis Fed

So, the federal government operates on negative income. It has to constantly borrow the difference. This is also a surplus for the private sector; it represents an ongoing addition of currency to the economy, which is part of the structural monetary inflation that occurs.

The government has a high debt/revenue ratio, and then also has negative income. If it were a company, that would put it down near the bottom of junk bond status at imminent default risk, rather than just normal junk bond status. The financial situation, if analyzed like a company, is abysmal.

But of course, the US federal government is not a company. Since the federal government issues its own currency and effectively controls its own central bank when necessary, it can’t nominally default unless by choice. When push comes to shove, it can have the Federal Reserve create an infinite amount of new base money to buy federal government bonds as needed, and hold interest rates below the inflation rate, and below the nominal GDP growth rate.

If the central bank (the Federal Reserve) resists this, which they likely won’t, then Congress can change laws and force the Federal Reserve to do it anyway. From 1942 to 1951, for example, the US Treasury effectively forced the Federal Reserve to monetize US Treasuries and hold interest rates at 2.5% despite running inflation at an average of 6% per year. This was the only prior time in US history where federal debt as a percentage of GDP went over 100%, and they resorted to repressing yields and inflating a large chunk of it away. During and after the subprime mortgage crisis and the COVID-19 stimulus bursts of spending, the Federal Reserve willingly monetized fiscal debt without being forced to, as part of its monetary policy toolkit.

Instead of actual default, the risk for this type of government debt is persistent currency debasement. Bond holders, cash holders, and bank depositors will sit there for years earning a rate of interest that is below the prevailing inflation rate, and as such their purchasing power will constantly be drained from them.

Suppose, however, policymakers try to avoid that scenario, and when inflation becomes severe, the Federal Reserve does indeed raise interest rates to try to contain it.

At $32.5 trillion in debt which we will get to in a couple years, every 1% of average interest rates on that debt (across weighted-average maturities) equals $325 billion per year in interest expenses. So, if interest rates on government bonds are 3% on average, they would be paying almost $1 trillion per year in interest alone. As such, the Federal Reserve is somewhat limited in terms of how high and persistently it can raise interest rates without causing the federal government to encounter a fiscal spiral, where their deficit blows out even further due to issuing debt just to cover the interest on existing debt.

Imagine a company with a 7.6x debt-to-sales ratio, with negative net income, and where interest expenses are a quarter of revenue and climbing. That’s what the government would look like in that higher interest rate scenario.

Is this fixable? Well, not really. Suppose the US were to raise revenue such that it takes in 20% taxes as a percentage of GDP, while cutting spending to 18% of GDP. The federal government would be running a 2% of GDP surplus, to try to reign in the national debt.

The vast majority of government spending is mandatory via past legislation, referring to Social Security and Medicare, as well as things like the military/veteran spending. All of that is politically unpopular to cut. The rest of the budget is a small fraction of the total budget. Some of those big items would need to be cut significantly to get to a budget surplus or even breakeven.

Often, a problem is that austerity is used out of order, in a way that is perceived as unfair. For example, during the subprime mortgage crisis, the troubled asset relief program and other fiscal measures bailed out the banker class more thoroughly than the homeowner class in the US. If austerity is attempted after that sort of decision, then the public perception rarely goes over well. People are like, “Oh, so we bailed out the bankers, but when the real economy needs help too, we don’t get it? That’s when we get fiscally responsible?” It’s a good recipe for rising populism.

But suppose policymakers get through that problem and implement fiscal austerity with debt already this high. With a 2% of GDP fiscal surplus out of $25 trillion in annual GDP, the government would be pulling in $500 billion per year in budget surpluses. With $32.5 trillion in debt, that would be a debt/income ratio of 65x, which is still terrible.

However, the actual situation is worse than that. The equation to calculate a country’s GDP is this:

GDP = C + G + I + NX

Where C is consumption, G is government expenditure, I is investment, and NX is net exports.

In other words, the current GDP number factors in government spending. If government spending shrinks and/or taxes go up, it is likely to significantly reduce GDP growth. Cutting spending significantly means cutting social security, Medicare, military, and similar large items. If taxes go up and/or spending goes down, that means a reduction in after-tax income for the private sector, and so people have less money to spend on goods and services. Plus, if asset prices go down, it results in a reverse wealth effect and people spend less, which is a problem considering the fact that consumer spending is over two thirds of GDP.

The government would be running a budget surplus, but likely with lower GDP, and thus ironically the debt-to-GDP ratio probably wouldn’t go down much, if at all.

That is why attempts at fiscal austerity usually fail if they are initiated after debt is already this high and wealth concentration is already this high. Fiscal austerity can work under normal conditions, when debt is low to begin with and society still has a strong social contract in place. But once debt is beyond a certain event horizon where the math doesn’t work anymore, there is basically no amount of spending cuts or tax increases that can persistently reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio without inflating a big chunk of it away. It’s like playing whack-a-mole, and the longer it is attempted, the angrier the population typically gets until they vote those politicians out of office in favor of an administration that promises not to do austerity. And then they get inflation instead, which the public also dislikes.

Either way, now that the math is where it is in terms of debt having reached unmanageable escape velocity, we’re probably stuck with the only option of the Federal Reserve holding interest rates below the prevailing inflation rate for a while. Hence, we see this:

The last time we had inflation-adjusted interest rates that negative was in the 1940s up through 1951, which was the only other time in US history where federal debt as a percentage of GDP was over 100%.

Furthermore, the US partially de-industrialized itself over recent decades, and began running large trade deficits with other countries. A larger share of our GDP began to consist of consumer spending.

As previously described, consumer spending is now over two-thirds of GDP:

Chart Source: St. Louis Fed

US household total net worth, due to very high equity and real estate valuations, is over 6x as large as the GDP:

Chart Source: St. Louis Fed

If asset prices fall (which they would almost certainly do if the government cuts spending and increases taxes), it would result in a reverse wealth effect, and probably weaken consumer spending, which would reduce GDP. It would also result in lower tax revenue, further contributing to the deficit that they would be trying to turn into a surplus.

Rather than asset prices reflecting the state of the economy, asset prices are so inflated that they can hurt the economy if they fall. It’s like the tail wagging the dog rather than the other way around.

The US fiscal deficit, as bad as it already is, actually has been lower than it would have otherwise been, thanks to the constantly-increasing asset valuations. Those increasing asset valuations fueled higher consumer spending and higher capital gains tax income. If those asset valuations stop going up structurally as they have been, it can quickly make the fiscal deficit a lot worse than it currently appears. Due to its large twin deficit (trade deficit and fiscal deficit), the US is arguably more vulnerable to this potential reverse wealth effect than most other developed countries.

When Does Government Spending and Taxation Work?

Government spending and taxation tends to be a very politically polarized topic. It’s near the core of what politics is.

Some people argue that the government should do a lot more spending to fix things. Other people argue that the government is always inefficient and that almost any spending they do is a waste.

It wasn’t always that polarized. For example, Democrats and Republicans in the 1950s generally agreed upon roughly the same set of facts as it relates to fiscal policy, and differed around the margins as to how to best deploy government resources. Nowadays, the two parties can barely agree what the facts are, let alone where to start in terms of crafting effective tax and spending policy. Everything is about political theater.

We do fortunately have a decent sample size of data to see that there is a spectrum here. Countries with very different policies ranging from Norway to Singapore have managed to prosper with very different government policies. Some have low taxes, and some have high taxes. All of them have some degree of market capitalism and social services. Countries that do well almost always have a high ease of doing business score, regardless of how much their government taxes and spends. This means that their regulations for setting up and running a business are quick and clear, there are low levels of corruption, and there is firm rule of law to enforce financial contracts.

Whether a country manages its debt well has less to do with the raw amount of spending and taxation, and more to do with the intelligence and efficiency of their spending and taxation.

Spending Examples

Extremes inform the mean, so we can imagine a hypothetical example of unanimously bad fiscal policy. Suppose the United States spent $1 trillion to make a ton of bombs and then drop them all in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. This would obviously be a massive waste. A few defense contractors would benefit from this and they would spend their extra income into the domestic economy, but there would be no persistent gain in terms of structurally higher GDP. Debt would be higher without structurally higher GDP, and so the debt/GDP ratio would get worse. We would also seriously mess up the oceanic environment, so it would be an ethical quagmire on top of being a financially imprudent thing to do.

On the other hand, the Interstate Highway System of the 1950s under President Eisenhower was an incredible investment. The government did the largest public works project in US history, and it substantially improved productivity throughout the United States. Transportation got a lot faster and easier, which lowered the costs of many types of goods and made businesses throughout the country more competitive and efficient. Because the spending was so productive, GDP went up by more than the debt that was issued to pay for it.

Today, the US could certainly use a revitalization of its infrastructure. This for example is a map of low-rated bridges in New Jersey:

Source: NJ.com

Most other states look like this too. There are thousands of bridges and tens of thousands of miles of roads that could use work throughout the US. Internet infrastructure could use an upgrade in many areas, and there are many other examples like this.

Historically, one of the least controversial areas of government spending is on infrastructure, although there are naturally big disagreements on what and how much to do, and it’s getting a lot more expensive over time due to various inefficiencies. The reasons that governments are often relied on for infrastructure spending is that private corporations usually have a 3-5 year capex cycle, and tend to get into financial trouble if they plan long beyond that, especially with leverage. For example, many of the companies that laid the undersea fiber optic cables in the 1990s went bankrupt in the process. The assets were extremely important for global connectivity for the following decades and counting, but the companies collapsed under the debt load when the economy went through an inevitable downturn. Similarly, the group that tunneled the English Channel eventually faced bankruptcy problems too.

It’s very hard to recoup the costs of projects of this scale within a business cycle, and instead they only make sense when spread out over longer periods. The world is lucky that many private pools of capital have attempted these projects anyway. If they were smarter, they probably wouldn’t have done them, and yet the world would be worse off for it.

Government can pool resources to do long-range infrastructure and research projects that might not pay for themselves for two decades or more, without risk of bankruptcy. However, it only makes sense if they are well-spent and well-managed. Besides the interstate highway system, a positive example in my view has been NASA; the list of technologies developed from their research is huge, and space travel inspired a generation of engineers to pursue the profession and enhance the country’s technology.

Taxation Examples

We can do a similar example for tax cuts. Suppose we don’t want the government to spend any more than they already are, but we have $1 trillion in tax cuts over a ten year period that we are allowed to do. Where should we best spend it?

We could give most of those tax cuts to the top 1% or top 10% in various ways. For example, we could cut corporate taxes again, which in all recent instances over the past twenty years, mainly resulted in accelerated share buybacks to improve shareholder returns rather than more capital investment. The top 10% of the population owns 89% of corporate equities in the US, so it would be a narrow gain. We could give billionaires and centimillionaires a personal income tax cut, but the problem is that they already spend very little of their income (there are only so many ways to consume money beyond a certain point afterall), so beyond buying additional luxuries, they will plow most of it into existing real estate, stocks, etc. It’s not as though there is a shortage of venture capital out there to fund startups with good ideas. Overall, this policy probably wouldn’t drive up much persistent GDP growth, even though it would expand the national debt by a lot. It would mainly just push up asset valuations and increase the level of wealth concentration in the country.

Chart Source: St. Louis Fed

Alternatively, in this era of record high wealth concentration, we could target the bottom 90% or so, and do a payroll tax cut with that money, so that tens of millions of workers can keep more of each paycheck. If we apply it to the employer side as well, then it also benefits companies (large and small) that employ a lot of people, and makes it more competitive to hire American workers rather than to rely on offshore production facilities. The majority of people will have more spending money, which will allow them to save more, and spend more around the economy. This would boost GDP, in addition to boosting national debt. This would benefit labor and benefit companies that employ a lot of labor and invest in the domestic economy, including indirectly benefiting the wealthy owners of these businesses too.

How it Works in Practice

But in practice, corporatism and government are intertwined. Policy is crafted from key lobbying input. My article on wealth concentration went into detail on some of the fiscal choices that led to the current situation.

The pendulum of power tends to swing back and forth until it reaches extremes. In the 1920s, those with capital (the “Robber Barons”) had maximum influence with politicians, and could craft legislation to further benefit their entrenched interests. The 1930s reached a breaking point and resulted in a shifting of the social contract, and the pendulum was pushed far in the other direction. By the 1970s, unions/labor had maximum influence with politicians to benefit their entrenched interests instead. This reached a breaking point as well, so they changed the social contract again and pushed the pendulum far in the other direction, and now the power is back with capital again. It seems as though it’s just starting to incline back towards labor.

From the 1950s into the early 1970s, debt as a percentage of GDP went down under both Democrat and Republican administrations. After that, it began going up structurally, and actually more-so under Republican administrations, partly due to fiscal policy choices and partly due to recession timings:

Most of the public wants taxes to be as low as possible and for spending on things that positively affect them to be high. Democrats usually try to increase spending and raise taxes to partly pay for it. Republicans usually cut taxes without cutting spending, and usually favor increasing military spending. There are some outlier politicians like Ron Paul that don’t fit cleanly in the parties and have attempted to cut both spending and taxes.

The combination of all of this is that the government keeps holding taxes relatively low while increasing spending, resulting in structural deficits that eventually lead to debt levels over 100% of GDP, at which point they need to be monetized by the central bank.

In particular, the wars in the Middle East were basically the “event horizon” for US fiscal policy, since they added trillions to the national debt without much of an increase to GDP. The use of force in Afghanistan was authorized almost unanimously, whereas the use of force against Iraq was more controversial but still passed comfortably with bipartisan support:

Source: Wikipedia

With the benefit of hindsight today, the numbers to which this added to US national debt were rather immense:

The costs of the post-9/11 wars are staggering, in blood and treasure. I am now going to address a corollary topic, which is: How have we paid for these wars?

The wartime budgetary process for the post-9/11 wars from 2001 to 2017 is the largest single deviation from standard budgetary practice in US history.

In every previous extended US conflict – including the War of 1812, the Spanish-American War, Civil War, World War I, World War II, Korea and Vietnam — we increased taxes and cut non-war spending. We raised taxes on the wealthy.

President Truman raised the top marginal tax rate to 92% during Korea. He believed it was morally right to “pay-as-you-go” – a term he coined and repeated in more than 200 speeches. President Johnson was more reluctant, but in 1967 he imposed a Vietnam War surcharge that raised top tax rates to 77%.

By contrast, in 2001 and 2003, Congress cut taxes – the “Bush tax cuts” as we went to war in Afghanistan and Iraq. Since then, we have paid for these wars by piling up debt on the national credit card. No previous US war was financed entirely through debt. I refer to these wars as the “Credit Card Wars.”

In addition, we have budgeted for these wars differently. In every previous major war, the war budget was integrated into the regular defense budget after the initial period. This meant that Congress and the Pentagon had to make trade-offs within the defense budget. By contrast, the post-9/11 wars have been funded mostly by supplemental appropriations.

The post-9/11 wars have been funded through emergency and Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) bills, which are exempt from spending caps and do not require offsetting cuts anywhere elsewhere in the budget. Over 90% of direct war spending for the current wars has been paid through supplemental money compared to 35% for Korea and 32% for Vietnam.

This process is less transparent, less accountable and has rendered the cost of the wars far less visible.

–Linda Bilmes, Harvard University, 2017 Congressional Briefing

When it comes to my analysis of monetary policy, fiscal policy, and inflation/disinflation in the United States from an investor point of view, I consider the US national debt as being beyond the point of recovery in any sort of real terms.

In other words, regardless of who is elected going forward, I view the range of policies that could potentially allow US government bondholders to be paid back with positive purchasing power to be vanishingly small. Neither Democrat nor Republican administrations will be able to solve the debt problem without holders of cash and bonds losing considerable purchasing power.

The same is true for the majority of other developed countries, to varying degrees. Japanese bondholders, Italian bondholders, Canadian bondholders- they are not likely to maintain their purchasing power over the next decade. And by extension, cash savers will not maintain their purchasing power over the next decade either, because their assets rely on the same interest rate policies.

So, Does National Debt Matter?

The short answer is yes, national debt matters, even when it’s denominated in a country’s own currency.

However, the way in which it can matter depends on the specific details.

When the debt is not denominated in a country’s own currency, the government risks actual nominal default if they handle their finances poorly.

On the other hand, when the debt is denominated in their own currency, the government almost always ends up printing the difference, holding interest rates below the prevailing inflation rate, and using capital controls or other restrictions to corral market participants into devaluing assets. The result is that bondholders and cash savers lose a big chunk of their purchasing power despite technically getting paid back. It’s a “soft” default, via inflation and financial repression.

Fiscal prudence is important when debt is low, because it helps prevent debt from getting too high before it happens. And this is not just in terms of how much spending and taxation are used, but also what types of spending and taxation. Is money being spent on defense and long-term productivity improvements? Is the tax arrangement suitable to entice employers to come to the country and hire domestic workers? Is the current social contract of the country relatively balanced, or is it out of whack with high levels of cronyism? Once government debt is beyond around 100% of GDP or so, the range of prudent policies gets narrower and narrower.

Navigating politics is always challenging from an investor standpoint. Investors tend to be overly optimistic when their preferred political party is in power, and overly pessimistic when their preferred political party is out of power. They tend to let their own political preferences shape their views on economic growth and inflation, even if their views are not necessarily backed up by evidence.

When I survey the fiscal situations of most developed countries, they seem to be in an unrecoverable fiscal position regardless of future election outcomes. Some fiscal choices are of course better than others (e.g. spending on domestic infrastructure or worker tax cuts rather than most types of war), but at this point it’s a matter of “damage control” and “choosing the least of multiple evils” rather than starting from a workable fiscal position. The situation is worse for countries with higher debt/GDP ratios, higher structural fiscal deficits, and/or higher structural trade deficits, but of course nonfinancial factors like natural resource endowments and policies regarding the ease of doing business matter significantly as well.

Investors that overweight cash and bonds in multiple currencies will likely be debased on persistent basis throughout the 2020s decade, although naturally there will be some years where holding those assets can provide protection against downturns in the prices of volatile assets. Cash and bonds are, in that sense, a very expensive form of optionality and volatility reduction, and little else.

Source link