The Global Race for a Centuries-Old Shipwreck and Its Billion-Dollar Treasures

June 8, 1708 the count of Casa Alegre knew a squadron of English warships was lurking in the area, but he thought he could avoid it. As captain of the Spanish galleon San José, he was charged with leading the Tierra Firma fleet from the Caribbean back to Spain, 17 ships in all, loaded with several years’ worth of treasure from the New World, enough perhaps to turn the tide of war in Europe. Casa Alegre had no doubt the English would be after the precious cargo. If he could reach the harbor of Cartagena de Indias, on the coast of what is now Colombia, the fleet would be safe.

Then they appeared on the horizon to the north. Four English sails. To give the fleet’s merchant ships a chance to reach the harbor, Casa Alegre had no choice but to turn and fight. He hoisted the red battle flag up the mainmast and sailed toward the enemy, accompanied by two armed galleons.

As in a bar brawl, the two most fearsome combatants sought each other out. At sunset, the 70-gun HMS Expedition, helmed by Commodore Charles Wager, took on the 62-gun San José. For more than an hour, they traded broadsides, sailing past each other while firing their cannons at close range, pulverizing wood and bone.

What happened next is unclear. Night had fallen, and the air was thick with smoke and the smell of gunpowder. Bellowed commands, screams of agony, and bursts of cannon fire resonated across the water. The English heard a powerful explosion from deep within the San José and felt the heat of the blast. A fire broke out on the ship, and soon the Spanish side went silent. By the time the smoke cleared, the galleon was gone. All that was left was a field of flotsam onto which fewer than a dozen young sailors clung for life.

It had sunk in a matter of minutes. Wager did not consider the battle a victory but a devastating failure. As the flagship, the San José carried far more silver, gold, emeralds, and pearls than any of the merchant vessels. Wager’s prize had slipped his grasp, and its treasure now gilded the seabed at unknowable depths, along with the bodies of Casa Alegre and almost 600 of his men.

In the three centuries since, the San José has become a myth. Its legend is built upon gold, which does not oxidize. A gold coin will shine as brightly after 500 years on the ocean floor as the day it was minted. So too in the imagination. The luster of gold from the New World entranced explorers from Columbus to Hernán Cortés, who is said to have told Montezuma’s messenger, “I and my companions suffer from a disease of the heart which can only be cured with gold.” That craving didn’t abate with time. In Gabriel García Márquez’s novel Love in the Time of Cholera, the lovelorn protagonist, Florentino Ariza, is stricken with “an overwhelming desire to salvage the sunken treasure [of the San José] so that Fermina Daza”—his beloved—“could bathe in showers of gold.” Colombia’s most celebrated author, García Márquez valued the treasure at “five hundred billion pesos in the currency of the day,” a magical realist embellishment.

Since no complete manifest exists, historians can only guess at the amount of silver and gold coins the galleon carried on its final voyage, including contraband: perhaps 7 million to 12 million pesos, believed by many to be worth more than $10 billion in today’s money.

Regularly referred to as the Holy Grail of shipwrecks, the San José had been the object of several extensive searches over the decades, becoming only more legendary the longer it remained undiscovered. And then, on December 4, 2015, Colombian president Juan Manuel Santos sent the following tweet:

Great news: We found the galleon San José! Tomorrow I will give the details at a press conference from Cartagena.

The next day, at the naval base in Cartagena, an exultant Santos touted the discovery as one of the most important “in the history of humanity” and promised to build “a great museum” to house the contents of the galleon. He said the search was a joint effort between the government of Colombia and an international team of scientists “of the highest level.” But he offered no specifics. Everything having to do with the San José, he said, was classified, including the coordinates of the wreck.

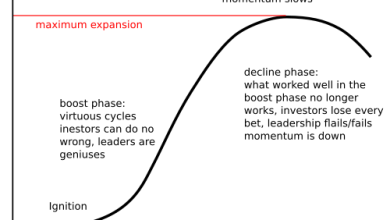

Elected in 2010, Santos had two grand objectives as president, say people familiar with his thinking. One was to end the war with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the Marxist guerrilla group that had terrorized the Colombian countryside since the 1960s. The other was to find and excavate the fabled San José. Santos won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2016 for securing the FARC’s surrender. Success with the San José would prove more elusive. If he had hoped the discovery would be an unadulterated legacy-cementing triumph, the passions unleashed in the wake of the announcement would quickly disabuse him of the notion.

More than 300 years after its sinking, the San José has become embroiled in a battle of a different kind, no less vicious, involving international high finance, treasure hunters, archaeologists, accusations of corruption, and elaborate conspiracy theories. At stake is not just a nation’s ransom in riches, but an archaeological godsend: As long as it is excavated with an eye toward science rather than lucre, the wreck can deepen our understanding of a period of colonial history that helped shape the Western Hemisphere.

In a radio interview shortly after his announcement, Santos offered tantalizing clues about the person behind the discovery of the San José. “I will tell you the tale,” he teased. During a consular event outside the country, he recalled, Santos had been accosted by “a man who looked like Hemingway…with white hair and a white beard.” The man had asked the president for two minutes of his time and offered him a framed copy of a large antique map. “He told me, ‘This map is not known to anyone,’ ” said Santos. “ ‘This site’—he showed me the site—‘does not appear on any other map and that site almost guarantees that I know where the galleon is.’ ”

Santos, who had been a sailor in his youth and made no secret of his love for the ocean, clearly relished the swashbuckling quality of the story. But when the interviewer pressed for more details, Santos allowed only that the mystery man “is not a treasure hunter. He’s not after money and he genuinely has an anthropological, historical, and cultural vocation.”

Questions abounded in the weeks that followed. Whoever “Hemingway” was, he had determined the search area, found the financing, and gotten into the president’s head. But who was bankrolling his operation? How much did it cost? Who stood to benefit? Was Colombia selling off its cultural patrimony? Was it even Colombia’s to sell?

Since the wreck had reportedly been found west of Cartagena in Colombian waters, Santos believed his government had the strongest claim to the galleon and its contents. Within days of Santos’s announcement, Spain’s minister of culture offered his country’s cooperation in salvaging the wreck while also invoking the principle of sovereign immunity, according to which a warship sailing under a nation’s flag remains that nation’s property even after it has sunk, regardless of how much time has passed. The Spanish foreign minister, José Manuel García-Margallo, issued a blunter warning: “If this cannot be resolved on friendly terms,” he told the press, Colombia “must understand that we will claim it and defend our rights.”

Santos didn’t back down. “There are a lot of owners who are now popping up,” he said at the time. “No sir, this is the Colombian people’s cultural heritage.” Rattling the ghost of the Spanish Empire has long been a winning political strategy in Latin America, so there was little incentive for Santos to give in. But what of other claims from Spain’s former colonies? Most of the gold and silver on board was loaded onto the San José in Panama and had been mined in what is now Peru and Bolivia. Peru had sued for its right to sunken Spanish gold before, arguing that colonists had stolen it from the land’s previous occupants. What was to stop it from doing so again?

Source link